Implantable and ingestible (edible) electronic devices that stay inside your body pose unique engineering challenges. These should not only use the best processor but also be minimal in size, biocompatible, safe and extremely reliable. Reliability is all the more important as it often turns out to be a case of life or death!

Despite so many risks and challenges, it is awesome to see how implants have developed since the days of the first pacemaker in 1958. From cardiac pacemakers to cochlear implants, from brain interfaces to retinal implants, there are numerous implantable medical electronic devices available today. Even more exciting is the emerging field of edibles—tiny, capsule-sized electronic devices that are consumed orally for diagnosis and treatment of diseases. Some edibles are designed to remain inside the body for some time, while others do their job and get disposed of within minutes.

Today, we have reached a state where inventions like these no longer surprise us because our minds have become tuned to a sci-fi future, and we have started expecting such developments. So let us put aside the wow-factor, and instead look at the current and future state of implants and edibles.

Painless diabetes testing, drug delivery and more

With improvements in quality and reliability, there is now a reasonably good demand for cochlear, retinal and cardiovascular implants. Cardiovascular implants have evolved much in recent years, and have overcome past constraints regarding compatibility with imaging systems such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Interestingly, the rise in lifestyle diseases like diabetes has also led to an increased demand for implantable devices like implantable continuous glucose monitoring and implantable infusion pumps. There are also implantable devices for phrenic nerve stimulation to restore breathing function in patients, and sacral nerve stimulation for patients with bladder disorders. Implantable neuro-stimulators, on the other hand, help those with neurological disorders like Parkinson’s disease.

With the availability of better biocompatible materials that minimise the possibility of infections, there is greater faith in implants. Researchers at the Graeme Clark Institute have developed an implant that is fitted under the scalp to diagnose and treat epilepsy, and even forecast a likely seizure. They are also developing an implantable drug pump for patients with drug-resistant epilepsy.

Cochlear implants are used when hearing aids don’t work well—that is, when the patient has severe sensorineural hearing loss due to absent or reduced cochlear hair cell function. The implant basically carries out the function of the cochlea or inner ear, stimulating the auditory nerve directly.

Retinal implants are giving vision to the impaired around the world. Going one step further, the Monash Vision Group is developing Gennaris—a bionic vision system that bypasses damage to the eye and optic nerve to restore functional vision for people who have injured both these or lost sight due to glaucoma and acquired retinal disease. This system interfaces directly with the brain, bypassing the retina and optic nerve.

Elsewhere, researchers are also exploring biocompatible, implantable photonic devices that can improve health monitoring, diagnostics and light-activated therapies. Consider the possibility of biocompatible and wirelessly-powered light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and miniature lasers implanted inside the body. Advances in biotechnology, such as optogenetics, will enable these photonic implants to be integrated tightly with neurological or physiological circuits.

A good interface between implanted devices and the brain can help in great ways—for example, it can return motor function to amputees and people paralysed due to stroke or spinal cord injury. A minimally invasive electrode called the Stentrode developed at the University of Melbourne might be a step in this direction. Implanted into a blood vessel adjoining the area of the brain that controls movement, it may help control an exoskeleton, enabling crippled or paralysed people to move. The implant can apparently be installed without opening the skull, which is what makes it attractive!

Neuralink, a company funded by Elon Musk, is also working on implantable brain-computer interfaces. They are developing syringe-injectable, flexible, sub-micron-thickness substrates that can be used in implantable electronics. The substrate is soft enough to sit harmlessly in the brain, and has electrical properties that enable only the targeted part of the brain to receive the electrical stimulus.

Brain-computer interface is the future of implantable systems. It can help people with degenerative brain diseases and neurological disorders. However, it must be handled with care because an electrode implanted in the brain can be used both for good and bad purposes!

Rise of edibles for diagnostics and drug delivery

When the electronic device needs to stay inside the body forever or for a reasonably long time, it is worth operating on a patient to implant the device. However, if you just want it to stay inside for a few minutes, hours or even days, for the purpose of monitoring a health condition or temporarily dispensing some medicines, operating on the patient doesn’t make sense. This requirement led to the development of ingestible or edible electronics, which industry-watchers expect to create huge waves like wearables did.

The electronics that you swallow, encapsulated in a pill, will sit in your gastrointestinal tract for a short time, before being ejected from your body like regular food waste. During this time it can capture videos, release drugs, monitor heart rate and respiration, and perform other such tasks.

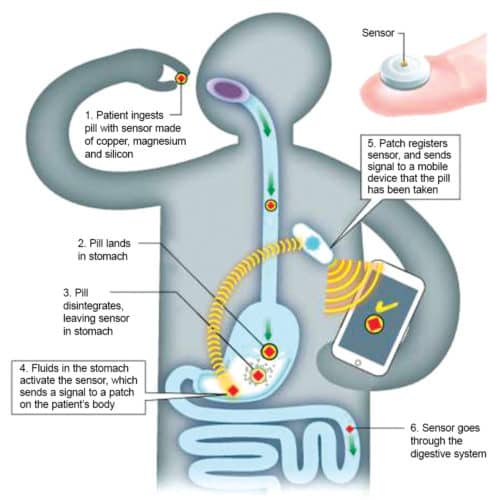

Proteus Digital Health was one of the pioneers in ingestible tech, and their technology is now used commercially by close to ten health systems. Their solution comprises a pill, a patch that is attached outside to the side of the stomach, and a mobile app/desktop portal. The pill is made of whatever drugs are required, and fitted with a sensor made of natural, ingestible materials like copper, magnesium and silicon. When a patient swallows the pill, it dissolves like a normal pill in the stomach but leaves behind a sensor, which is activated by fluids in the body. This sensor sends a signal to the patch, which also measures heart rate, body position and time of medication detection. This information is sent to the patient’s or doctor’s mobile phone.

Regular drug intake is very important for those undergoing complex medical treatments such as organ transplants. This pill could be very useful for such patients. Proteus has teamed up with Tokyo-based firm Otsuka to embed Proteus’ sensors into Abilify—a drug used for serious mental illnesses.

Another forerunner in the space is Israel-based Given Imaging. Their PillCam series comprises pills with ingestible cameras, which can help doctors to view different parts of the patient’s digestive system like the oesophagus or colon. It is a painless alternative to tests like endoscopy and colonoscopy. The PillCam Colon, for instance, uses a battery-powered camera to take high-speed photos as it slowly goes down the intestinal tract over a time period of eight hours. The images are transmitted to a recording device worn around the patient’s waist and later reviewed by a doctor. Although the images are not as sharp as those obtained through normal colonoscopy, it is a viable alternative for those who cannot bear the pain or feel embarrassed by the procedure.

Other versions of PillCam help doctors to see the small intestine and oesophagus. The company has also developed SmartPill—an ingestible capsule that measures pressure, pH and temperature as it travels through the gastrointestinal tract. This helps doctors to assess GI motility.

Bravo pH is another capsule-based test that helps to test for acid reflux. The miniature pH capsule attaches to the oesophagus and sends pH data wirelessly to a small recorder worn on a shoulder strap or waistband. Information is collected over multiple days, enabling doctors to study the frequency and duration of acid flowing back up into the oesophagus. This helps to confirm the presence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). This is a totally catheter-free solution, so the patients can go about normal activities and have a normal diet while the pill unobtrusively monitors their acid reflux. They can remove the receiver to take a shower. This type of monitoring under a normal routine gives better results than keeping the patient under observation.

Unique engineering challenges

The most obvious challenge to edible electronics is, obviously, miniaturisation. It is impossible to implant or consume something that is bulky. With the electronics industry in general moving towards miniaturisation in everything, this goal has become more achievable in implantable devices, too. Unlike the traditional pacemaker, the newer leadless pacemakers are about the size of a large capsule, and can be placed directly in the heart. These can be implanted through a femoral vein puncture in about half an hour. No more bulges or scars, these pacemakers are very unobtrusive and apparently also less prone to infections. The National Heart Centre Singapore (NHCS) began implanting such pacemakers last year.

Thermal management is another huge challenge in implantable devices. Like any other electronic device, implantable devices too vent out waste heat. However, this heat should not harm the surrounding tissues. So while designing an implantable device, engineers have to consider thermal properties of biomaterials, the effect of blood flow on temperature distribution, interfacial contact resistance, effect of temperature change on various types of tissues and communication duty cycles of embedded electronic components.

Further, the in-vivo electronic device must be biocompatible—it must not cause any adverse reaction inside the body. It must be stable over time, despite the temperature and pH variations in the human body. The biocompatible materials must not contain cancer-causing toxins, and must mostly be made of materials naturally suitable to the human body. The insulation materials must match the texture and smoothness of the surface they interface with, be it tissue, bone or skin.

Currently, we have biocompatible polymers for use in drug delivery devices, skin or cartilage and ocular implants; metals for dental and orthopaedic work; semiconductor materials for bio-sensors and implantable microelectrodes; and ceramics for bone replacements, heart valves and dental implants. But, ingestible electronics adds to the constraints, requiring the device and its power source to be made of materials that are part of our diet and can be disintegrated and disposed of easily by the body.

The search is on

There is a lot of ongoing research on bio-inspired, biocompatible materials and power sources, which can improve the performance and reliability of implantable and ingestible devices.

A recent paper by MIT researchers, published in Nature, describes a biocompatible power source that lasts much longer than current options that can power the edible device only for a few minutes or at the most a few hours. This energy-harvesting galvanic cell for continuous in-vivo temperature sensing and wireless communication could deliver an average power of 0.23µW per square-mm of electrode area for an average of 6.1 days, when used for temperature measurements in the gastrointestinal tract of pigs.

In yet another development, Dr Christopher Bettinger of Carnegie-Mellon University proposed biodegradable elastomers as structural polymers, and melanin-based pigments as materials for on-board energy storage in implantable and ingestible electronics. His lab focuses on the development of biomaterials-based micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) for use in regenerative medicine, neural interfaces, drug delivery, etc. They have developed edible, biocompatible batteries that use non-toxic materials already present in the body, with available liquids such as stomach acid as the electrolyte. Their cathodes use melanin, while anodes are made of manganese oxide. These electrodes dissolve harmlessly after use.

A team of researchers, including Zhaowei Guo and others from Fudan University in China, have developed a family of flexible and biocompatible aqueous sodium-ion batteries for implants. Instead of toxic electrolytes, these batteries use sodium-containing aqueous electrolytes such as normal saline and cell-culture medium. The cell-culture medium comprises amino acids, sugars and vitamins, which is quite similar to the fluid that surrounds cells in the human body.

The team made two kinds of batteries. One was a two-dimensional belt-shaped battery made of thin films of electrode material stuck on a mesh made of steel strands. The other used a woven carbon nanotube fibre backbone with embedded nanoparticle electrode materials.

This fibre-shaped electrode with normal saline or cell-culture medium electrolyte surprised the researchers by accelerating the conversion of dissolved oxygen into hydroxide ions, and changing the pH. While this could be detrimental to the effectiveness of the battery, it could be very useful in biological and medical investigations like cancer starvation therapy.

In Stanford, a team led by Zhenan Bao has developed a flexible electronic device that can easily be degraded into non-toxic compounds just by adding a weak acid like vinegar to it. Apart from the polymer and the degradable electronic circuit, the team has also developed a new cellulose-based biodegradable substrate material for mounting the electrical components. According to them, this substrate supports electrical components, flexing and moulding to rough and smooth surfaces alike.

Bao is not new to this field. Human skin has always fascinated her, and she previously developed a skin-inspired stretchable electrode, which was so flexible that it could easily interface with the skin or brain. However, the electrode’s non-degradability made it unsuitable for implantable devices.

Bao says in a media report that they came up with an idea of making these molecules using a special type of chemical linkage that can retain the ability for the electron to smoothly transport along the molecule. But this chemical bond is sensitive to weak acid—even weaker than pure vinegar. So the result was a polymer material that could not only carry an electronic signal but also break down easily to product concentrations much lower than the published acceptable levels found in drinking water.

How do sensors made of biocompatible materials compare with those made of food itself? Well, obviously you would prefer the latter. So thought a team of researchers from the University of Wollongong in Australia! In a paper, they reveal that the development of highly swollen, strong, conductive hydrogel materials is necessary for the advancement of edible devices. So they analysed the electrical properties of everyday food products like jelly, Vegemite and Marmite (two popular brands of yeast extract) and harnessed them to make edible hydrogel electrodes. These gels were used to demonstrate a capacitive pressure sensor that can help detect digestive pressure abnormalities such as intestinal motility disorders.

Eat your robot

We have biocompatible materials as well as transistors, sensors, batteries, electrodes and capacitors made using such materials. So you might think, why not a robot, too? But, what sets a robot apart from other computing systems is its ability to move—a robot needs an actuator, and attempts at making an edible one have been unpalatable all along!

Switzerland-based research organisation EPFL has made some headway recently. At a conference held this year, researchers led by Dario Floreano presented the prototype of a completely edible, soft, pneumatic actuator made of gelatin, glycerin and water. The design and performance of this new gelatin actuator is comparable to standard pneumatic actuators. Its structure causes it to bend when inflated and straighten out again when pressure is reduced. The main benefits are that it is edible, biodegradable, biocompatible and environmentally sustainable. Since gelatin is melty, the actuator also turns out to be self-healing!

The researchers explain several exciting applications for this actuator. The components of such edible robots could be mixed with nutrients or pharmaceutical components to improve healing, digestion and metabolism. These can be used as disposable robots to explore, study the behaviour of wild animals, cure sick animals or train protected animals to hunt. These can also be used in relief measures. In search-and-rescue operations, the robot can be sent without a payload to stranded people as the robot itself is food!

But can we pay the bills?

A recent Frost & Sullivan report noted that the fastest growing segment amongst the many types of implants is implantable neuro-stimulators, which help treat neurological disorders such as epilepsy, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and dystonia. It is also likely that in the future, these implantable electronics will be digitally connected to improve the scope of remote drug delivery, testing and diagnostics.

The cost of researching and developing implants continues to be high due to the criticality and complications involved—and often this cost reflects in the end price points. In the report, Frost & Sullivan industry analyst Bhargav Rajan noted that the constant stream of innovations has attracted substantial private funding to the implantable electronics market, while public funding is expected to improve in the future. He also suggested that technology developers can lower development costs by collaborating with early-stage start-ups and small- and medium-sized enterprises. This will allow them access to cross-industry expertise and cutting-edge innovations, which, in turn, will help lower the price points.

A majority of the population seeking implants belongs to low- and middle-income groups. Taking note of this factor, the report also stressed that the growth of this sector depends not entirely on technological development but also the availability of insurance coverage and reimbursements for such devices.