A couple of years ago, India dreamt of becoming a hub for electronics product manufacturing. Today, let’s assess the reality of that dream and identify the key components required to transform it into a substantial industry

The World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Information Technology Agreement ushered in a new era for Indian consumers in 1997, granting access to global consumer electronics brands and cutting-edge technology at competitive prices.

From the iconic Sony Walkman, which revolutionized music on the go, to the ubiquitous smartphone of today, these devices have become integral to our lives.

However, the influx of foreign consumer electronics brands did not bode well for prominent domestic brands such as Onida, Videocon, BPL, Zenith, etc, who struggled to achieve comparable scale and value addition.

Interestingly, the entire electronics market was not rattled by this wave.

Certain sectors, such as industrial electronics (energy meters and inverters) and 2-wheeler automotive electronics, remained relatively less impacted by the influx of global brands.

This was because these two realms of electronics already had a local ecosystem that designed, manufactured, and produced components domestically.

These indigenous manufacturers found a robust market by supplying their products to renowned energy meters and utility companies and automakers such as Bajaj, TVS, Hero, etc, enabling them to maintain their foothold in the Indian market.

Ambitious Goals and Current Realities

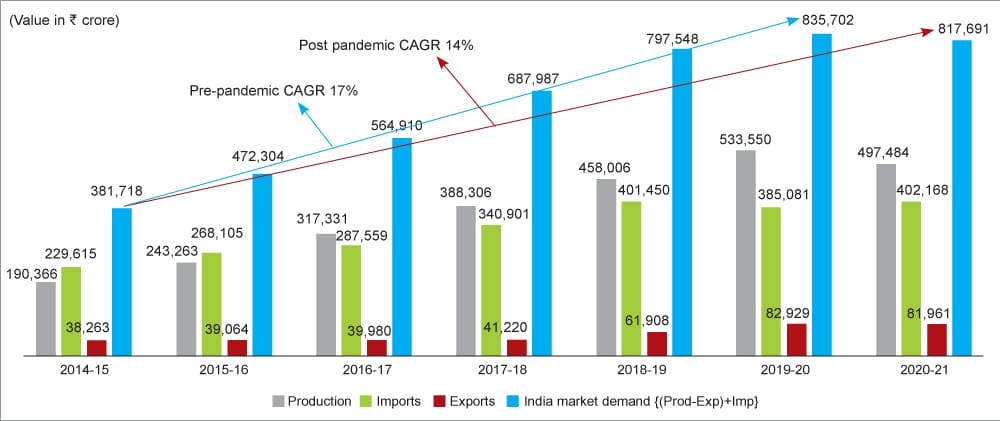

Fast forward to today, India’s electronics manufacturing industry is ambitiously aiming for a $300 billion target output, with a hopeful projection of $120 billion in exports by the financial year 2026-27.

This growth trajectory aligns with the country’s broader vision of achieving a $1 trillion digital economy by 2025. While these goals are inspiring, it is important to acknowledge a crucial aspect: India continues to heavily rely on electronics imports to meet its domestic demand.

Rising input costs due to high imports, coupled with surging domestic demand for consumer electronics, have now, more than ever, created a pertinent need for an electronics manufacturing ecosystem that adds high value to India’s local component manufacturing capability.

Learning from Global Players

As India scales up resources to encourage consumer electronics companies to ‘Make in India’, its neighbors have become the front-runners in electronics manufacturing for more than four decades.

The Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER) released a report that underlines the potential for India to learn from the success stories of China and Vietnam in the electronics sector.

During the early ecosystem-establishing days, the two countries prioritized exporting at scale to the global market, over achieving high levels of domestic value addition. Both countries focused on attracting foreign investments by offering a large and relatively low-cost labor force.

China went the extra mile to increase domestic value addition by investing in research and developing technical capabilities to become a key player in manufacturing high-tech components, from primarily being an assembler. With this approach, it took China 40 years to achieve exports worth $900 billion!

| DVA = Total Exports×DVAratio where, DVA refers to the total value of domestic inputs used in exports; DVAratio refers to the domestic value addition per unit of output (or total demand). To increase the DVA of smartphones, one could increase the number of smartphones exported or the DVAratio in each smartphone, say from 25% to 75%. By this logic, if both SCALE and RATIO can be increased simultaneously, it would lead to an even higher DVA and hence, faster job creation. (Source: ICRIER Report, Globalise to Localise) |

If we compare the starting points of India, China, and Vietnam in the electronics sector, the East-Asian countries possessed a more robust manufacturing base and export-oriented industries from the outset, only after which they built a competitive domestic ecosystem and technical capabilities.

This ultimately resulted in higher participation in global value chains, increasing their share of domestic value addition in exports. On the other hand, India had to focus on skill development and workforce training to meet the demands of the electronics industry.

Competing with Chinese global value chains worth $900 billion seems like a fool’s errand, but India has been taking significant steps to establish a competent domestic manufacturing ecosystem, in the form of incentives and developing electronics manufacturing clusters.

The question is, how effective are these schemes in increasing local value addition?

The Catch-22 of PLI

To catch up with the success of China and Vietnam, the Indian government introduced the production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme for mobile phones and large-scale electronics manufacturing, with mobile phones being the ‘belle of the ball’.

“We must shift our focus to ‘higher value addition,’ which can be accomplished by developing a local component manufacturing ecosystem, contributing 40% of the value, and investing in local IP and technology development, which adds another 30%.”

—Sanjeev Keskar, Industry Expert and

former Managing Director, Arrow Electronics, India

As a part of her Budget 2024 speech, Finance Minister Niramala Sitharaman announced that mobile phone production in India had increased from 58 million units valued at about ₹189 billion in 2014-2015 to 310 million units valued at over ₹2,750 billion in the last financial year, as a result of various government initiatives, including the phased manufacturing program.

The PLI for IT hardware has benefitted companies such as Dell, Optiemus Electronics, Dixon, Bhagwati Products, etc. The PLI for the large-scale electronics manufacturing (LSEM) sector has attracted leading global players, including Foxconn, Samsung, Pegatron, Rising Star, and Wistron, while leading domestic companies, including Lava, Micromax, Optiemus, United Telelinks Neolyncs, and Padget Electronics, have also participated in this scheme.

Despite the whopping numbers for mobile phone exports, India relies heavily on imports for crucial components. The scheme prioritizes the assembly of mobile phones over manufacturing the complete-knockdown (CKD) kit in India.

In addition, it is no secret that the incentive implies that the government pays all manufacturers in India—irrespective of nationality—6% of a phone’s invoice price, coming down to 4% in the fifth year for every incremental unit produced in India.

This, along with the tax incentives, power, and land subsidies offered by the state governments, amount to a mammoth expenditure on the State’s part.

However, the question remains—How much value is added to India through this expenditure?

To answer that question, we dive deeper into the pool of numbers. Reports from the Electronics Industries Association of India (ELCINA) show that the import dependency has reduced from 60% to 40%.

Out of the total $120 billion worth of electronics products demand, almost $80 billion was domestically manufactured, while $40 billion were finished goods imports in 2022.

Wonderful news, isn’t it?

However, what most reports fail to mention is that out of the $80 billion of products that have been domestically manufactured, only 15% of the total electronics used have been locally manufactured.

So, eventually, India earns approximately $12 billion in an electronics market worth $120 billion. This is because the subsidy is paid only for finishing the phone in India, not on how much value manufacturing in India adds.

Industry expert and former Arrow Electronics, India, Managing Director Sanjeev Keskar explains this further. He says, “If we import CKD kits of mobile phones and only perform SMT assembly in India, it results in less than 10% of value recognition, and to achieve even that, we are offering a 4% PLI incentive.

Addressing Challenges, Unlocking Potential

In the long run, this strategy is not viable. Instead, we must shift our focus to ‘higher value addition,’ which can be accomplished by developing a local component manufacturing ecosystem contributing 40% of the value, and investing in local IP and technology development, which adds another 30%.”

“We possess exceptional talent in semiconductor chip VLSI and embedded electronics design. However, much of this talent is employed in captive design centers of global companies or design services firms. While we secure jobs, we often miss out on the intellectual property (IP) value they create.

Therefore, it is imperative to prioritize the success of Indian startups in chip and embedded electronics design in conjunction with developing a robust local component ecosystem. Relying solely on manufacturing CKD kits would prove disastrous in the long run,” Keskar says.

The proposed timeline for achieving the $300 billion target is the financial year 2026—with the current rate of domestic value addition, 15-20% for mobile phones and 25-30% for other electronic components.

These numbers currently fall short of the target of 35-40% and 45-50% set by the PLI scheme for mobile phones and electronic components.

Even though electronics exports and domestic consumption have increased by 14% over the last six years, data from ELCINA shows that the Indian component industry continues to face direct and indirect opportunity losses.

The report collated data from the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) and ELCINA’s estimates, showing that $121 billion worth of electronics equipment was made in India in 2022-23.

To meet this demand, $52 billion worth of components were required but only $3 billion worth of components were produced domestically.

Keskar explains, “In any electronics product, components contribute approximately 40% of the total value, 25% for semiconductors, 10% for passives, connectors, and cables, and 5% for bare PCBs.

With a projected $300 billion growth potential, the demand for passive components and bare PCBs is expected to reach around $30 billion and $15 billion, respectively, both of which are predominantly imported currently.

Unlike semiconductor fabrication labs, assembly, testing, marking, and packaging (ATMP) facilities, passive components, and PCBs do not require massive investments.”

Global electronics products rely heavily on passive components, accounting for about 48% of the components, and active components comprise the remaining 52%. The Confederation of Indian MSMEs in ESDM and IT (CIMEI) Director-General Jairaj Srinivas believes India can manufacture simple components such as transformers, capacitors, and transistors.

“These components do not require extensive expertise. By encouraging and supporting local production of these passive components, India can create a self-sustaining ecosystem for the electronics industry and reduce dependence on imports, fostering domestic manufacturing,” he adds.

Currently, the government has introduced the Scheme for Promotion of Manufacturing of Electronic Components and Semiconductors (SPECS) to support the manufacture of passive components and the PCB sector.

“Under this scheme, a 25% incentive on capital expenditure investment is offered for manufacturing these products, following a reimbursement policy. However, there is a need to modify this scheme to encourage wider participation, including MSME industries. With a projected $45 billion opportunity in the next five years, this sector holds immense potential and can significantly contribute to India’s electronics manufacturing capabilities,” Keskar adds.

Salvaging the Squirming Sector

The domestic electronics manufacturing sector is squirming to compete with the likes of Wistron and Foxconn, who, with their gargantuan resources, have set up massive assembly units but continue to import essential electronics components.

Creating a level playing field for domestic manufacturers by reducing the bureaucratic red tape for infrastructure expansion, boosting intellectual property (IP) creation, and investing in research and development of embedded electronics products can contribute to almost 30% of the value in the electronics industry.

Infrastructure

These opportunities can be availed to ensure the success of Indian MSMEs that design electronics products in India and electronics design-as-a-service startups, by creating pathways to quality infrastructure and access to funding to establish huge manufacturing facilities to compete with the industry behemoths.

In April 2020, the government of India announced the Electronics Manufacturing Cluster 2.0 (EMC 2.0) Scheme to establish a complete ecosystem for ESDM manufacturing/production.

While many may welcome this move, the EMC 2.0 Scheme fails to provide specific details about whether it provides investment for assembly or manufacturing units.

Srinivas says that under the scheme, CIMEI has signed an MoU with the Uttar Pradesh state government, requesting 500 acres of land from the government to set up a complete electronics manufacturing ecosystem.

As per the scheme, the government will bear the majority of the costs for land development and setting up a common facility center.

“The production-linked incentive for the components is yet to be finalized. However, we have spoken to nearly 15 companies in Taiwan and China interested in setting up their manufacturing units as joint venture partners in India. Under this arrangement, the Indian partner will hold a 51% stake, and the foreign partner will hold 49%. This ensures that India has a major stake in the organization, and manufacturing will occur within the country, thereby strengthening the supply chain and minimizing disruptions, especially in component-level manufacturing,” adds Srinivas.

“Passive components account for about 48% of the components, and active components comprise the remaining 52%. To foster domestic manufacturing, India can manufacture simple components such as transformers, capacitors, and transistors, which do not require extensive expertise.”

—Jairaj Srinivas, Director-General, The Confederation of Indian MSMEs in ESDM and IT (CIMEI)

Research and Development

One of the main reasons India’s neighbors accelerated their lead in the electronics revolution was the focus on developing technical capabilities. In contrast, India’s current spending on research and development in the MSME sector is only 2.5%.

Small businesses often struggle to allocate funds for research and development due to limited financial resources. Despite having Centres of Excellence for different electronics domains and various incubation centers, the success rate for startups and small businesses working in the ESDM industry remains low.

To promote collaborative efforts with respect to research and development, Srinivas suggests collaboration and engagement by companies with substantial financial resources and significant corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds to invest in R&D initiatives.

“These companies can contribute to the development of common facilities centers and establish contract research organizations that cater to various sectors, including the ESDM sector and beyond. Small businesses can access research facilities without incurring substantial costs through such research opportunities, thereby promoting R&D activities,” he adds.

| While manufacturing abilities may take some time to develop, harnessing what is in hand can help strengthen the sector. With many design houses and startups, incentivizing design activity in India through the Design Linked Incentive (DLI) scheme will attract domestic and global players in the semiconductor industry. The scheme provides financial and infrastructural support to companies setting up fabs or semiconductor-making plants, encouraging innovation, reducing dependence on foreign manufacturers, and boosting India’s position in the digital revolution. The DLI scheme consists of three components: Chip Design Infrastructure Support: C-DAC will establish the India Chip Centre to provide state-of-the-art design infrastructure and facilitate access to supported companies. Product Design Linked Incentive: Approved applicants engaged in semiconductor design can receive up to 50% reimbursement of eligible expenditures, with a ceiling of ₹150 million per application. Deployment Linked Incentive: Approved applicants deploying semiconductor designs in electronic products can receive an incentive of 6% to 4% of net sales turnover over 5 years, with a ceiling of ₹300 million per application. So far, seven startups with product applications ranging from artificial intelligence (AI) to vector processes and image sensors have been approved for funding. The scheme is part of the $10 billion India semiconductor mission announced by the government in 2021. |

The electronics components market in India measures up to $64.2 billion, of which a significant amount continues to be imported. To reduce dependency on imports and become truly Atmanirbhar in the ESDM sector, initiatives such as the design-linked incentive scheme, for MSMEs and startups, propel manufacturers to increase domestic value addition, ultimately creating a high-value-addition electronics industry and generating employment in electronics component manufacturing.

While the PLI schemes encourage investments in the sector, there is a dire need to establish and treat the components industry differently regarding incentives. A longer gestation period and a smaller investment-to-sales ratio call for extended incentive periods to ensure a positive return on investment in component manufacturing for investors.

With nearly 50% of value addition in the component ecosystem, focusing on localized manufacturing can boost the nation’s overall economic growth and resilience.

While the Sony Walkman may be long gone and forgotten, we can certainly hope that soon enough every smartphone will have the majority, if not all, of the components completely manufactured, and not just assembled, in India.

The author, Yashasvini Razdan, is a Technology Journalist at EFY