A Prototype switch built in nanoscopic level can increase efficiency of electronics devices by reducing the heat it generates.

Research team at the University of Michigan has built a prototype switch to reduce the heat inside electronic devices during runtime. The design points the way to cooler and 66 percent more efficient than traditional electronic switches.

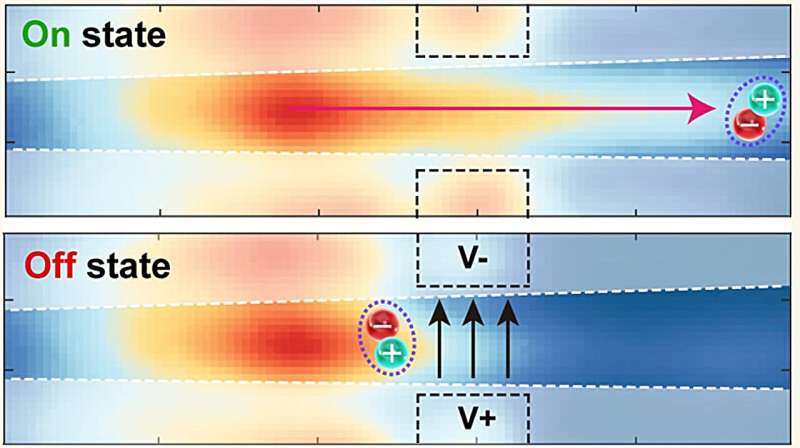

The new switch doesn’t rely on the usual flow of electricity through wires. Instead, it creates tiny paired particles inside an ultra-thin nanoengineered optoexcitonics (NEO). These pairs then steers along a narrow path into the surface of the chip. This path works like a gate: it can let the pairs through when the switch is “on,” or stop them when the switch is “off.”

Instead of relying on electrons, the device works with excitons; paired particles formed when an electron leaves its position and the gap it creates binds with it. Excitons do not carry charge, so they avoid much of the energy loss that electrons produce.

Electronic devices heat up as moving electrons face resistance while electrons flow through circuits. This resistance turns part of the electrical energy into heat, reducing efficiency and limits performance. The new switch cuts these losses by two-thirds while matching the performance levels of the best switches in use.

The research team have solved this by placing a single layer NEO of Tungsten Diselenide (WSe2) on top of a tapered ridge of Silicon Dioxide (SiO2). The structure steers excitons in one direction, helping them travel farther and faster than before. It also created a barrier that could block or release their flow, giving the switch its on–off function.

The design allowed researchers to address long-standing challenges by creating strong interactions between light and non-emitting, or dark, excitons. This interaction produced a quantum effect that moved the entire exciton population more efficiently, enabling transport up to four times greater than existing exciton guides.

The exciton–light coupling also generated a force that formed an energy barrier, which could stop exciton flow to switch the signal off and be reversed to turn it back on. At the same time, the tapered nanoridge in the device acted as a guide, steering excitons in a controlled, single direction.