A new “Swiss-roll” neural probe design promises 3D brain mapping with flexible electronics, offering richer neural data, reduced tissue stress, and potential breakthroughs in prosthetics and bionic vision.

A new generation of brain probes could transform neuroscience by enabling researchers to map neural activity in three dimensions rather than along flat planes. Scientists from Dartmouth College, the University of Pittsburgh, Oklahoma State University, and collaborators have developed a technique to roll flat soft electronics into cylindrical forms, creating 3D neural probes that overcome the restrictions of conventional 2D layouts. Reported in Nature Electronics, this innovation—called ROSE, or rolling of soft electronics—offers a way to record richer data with less tissue stress.

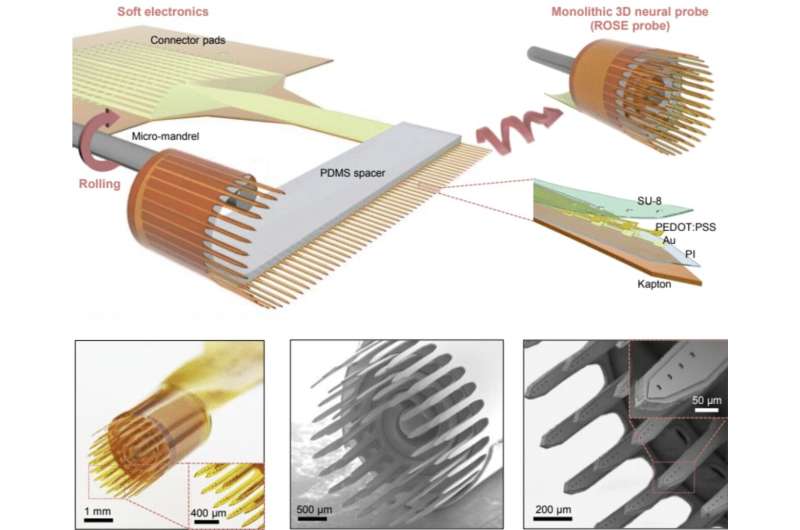

Traditional neural probes, built on rigid semiconductor processes, are confined to flat electrode arrangements, limiting how many neurons they can track simultaneously. The ROSE approach instead produces dense arrays of electrode shanks embedded in flexible cylindrical structures, with tunable spacing, pitch, and recording depth. The design resembles a “Swiss roll,” where each outward-pointing shank serves as an electrode. This flexibility allows hundreds of recording sites on a single probe, capturing neural activity at multiple depths while minimizing inflammation.

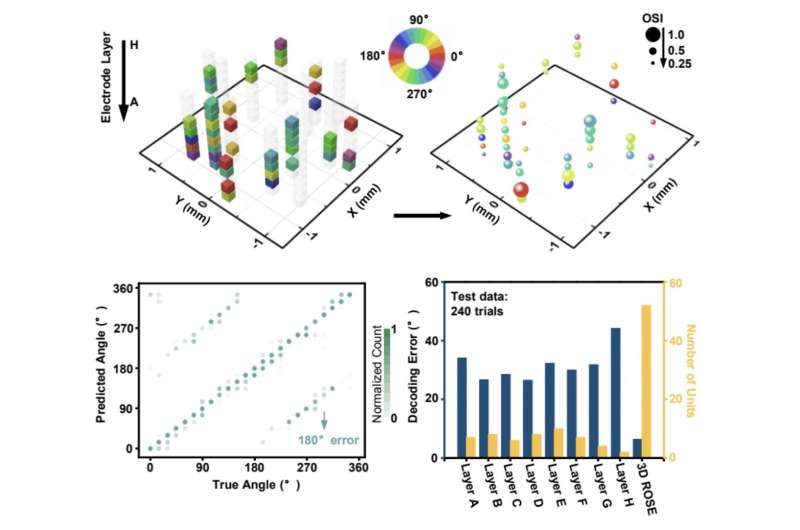

The features stand out: a 3D cylindrical form with customizable arrays, multi-site electrode positioning, and mechanical compliance that reduces brain tissue damage. Compared with the Utah Array—the current gold standard—ROSE probes deliver depth profiling instead of just surface-level recordings. Early demonstrations in awake rodents showed that the probes improved decoding of orientation tuning, while causing less stress to surrounding tissue.

The advantages extend beyond the lab. By generating higher-resolution maps of neural circuits, these probes give researchers better tools to understand how populations of neurons coordinate behavior. Clinically, their potential reaches into next-generation motor prosthetics, where brain signals could drive robotic limbs with greater precision, or even into bionic vision systems that restore partial sight. Future work will focus on improving long-term stability and biocompatibility, moving from short-term experiments to chronic implantation. If successful, rolling soft electronics could equip neuroscience with the long-awaited tools to probe the brain in 3D detail, paving the way for both fundamental discoveries and transformative therapies.