Making hydrogen is hard at high heat because normal membranes break. A new palladium plug design separates hydrogen without cooling, cutting cost and complexity.

Hydrogen production processes face a key challenge in separating hydrogen from other gases at high temperatures. Conventional palladium membranes work up to about 800 kelvins but above that they degrade, forcing systems to cool gases first, which adds cost, energy use, and hardware.

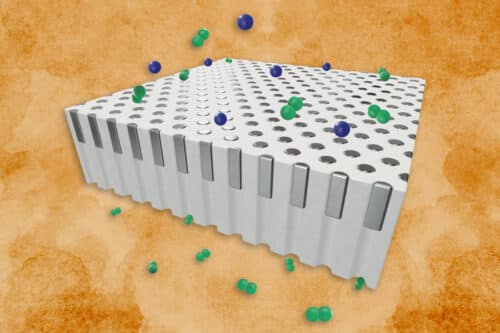

MIT engineers have developed a new palladium membrane that overcomes this limitation. Instead of a continuous film, the membrane uses palladium plugs inserted into the pores of a supporting material. These plugs remain stable at high temperatures, maintaining hydrogen selectivity without degrading.

This design could benefit high-temperature hydrogen processes such as steam methane reforming and ammonia cracking, helping generate hydrogen for fuel and electricity. In these applications, the ability to separate hydrogen without cooling the gas first reduces reactor size, complexity, and cost.

The design emerged from a project on fusion energy. Future fusion power plants will circulate hydrogen isotopes at high temperatures to produce energy through fusion. These reactions generate other gases that must be separated, and the hydrogen isotopes are recirculated. Similar challenges exist in other hydrogen-producing processes where gases must be separated and returned to a reactor.

The new approach uses a porous support material plugged with palladium deposits. At high temperatures, palladium normally shrinks and forms droplets, but pre-forming it inside pores maintains membrane integrity while increasing heat tolerance.

Small membranes were made using a porous silica layer with pores about half a micron wide. A thin palladium layer was deposited and grown into the pores, leaving palladium only inside. Testing showed the membranes remained stable and continued to separate hydrogen from other gases at temperatures up to 1,000 kelvins for over 100 hours, which is an improvement over conventional membranes.

This design extends palladium’s heat resilience by about 200 kelvins while keeping structural integrity under extreme conditions. The membranes perform within the temperature ranges of hydrogen-generating technologies such as steam methane reforming and ammonia cracking.

Further development and testing are needed to ensure reliability in reactors. The plug-based design shows a path toward stable membranes that use less palladium while enabling hydrogen separation at high temperatures.