Regular cameras trade off detail, size, and distance. This new system skips lenses, using sensors and computation to capture tiny details clearly from far away.

High-resolution optical imaging has long been limited by the trade-offs of conventional lenses. Achieving fine detail usually requires complex optics, precise alignment, or sacrificing field of view and working distance. These constraints make tasks like forensic analysis, industrial inspection, medical imaging, and remote sensing difficult when sub-micron resolution is needed over a wide area.

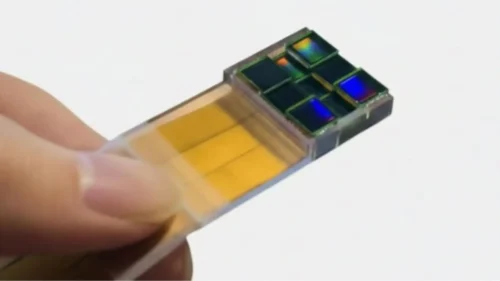

A new imaging system from the University of Connecticut addresses these problems by achieving optical super-resolution without lenses. Instead of relying on physical optics, the system uses computation, sensor arrays, and advanced algorithms to overcome limits that have constrained imaging systems for decades.

The approach builds on principles from the Event Horizon Telescope, which combines data from multiple radio telescopes to simulate a larger aperture. Translating this to visible light was previously impractical because optical wavelengths are much shorter, making tiny misalignments between sensors destructive to image quality. MASI (Multiscale Aperture Synthesis Imager) avoids this issue entirely: each sensor independently measures light, and computational algorithms combine the data afterward to form a single coherent image.

MASI replaces lenses with an array of coded sensors placed in a diffraction plane. Each sensor captures raw diffraction patterns, recording both brightness and phase information. These measurements are processed to reconstruct complex wavefields, which are then digitally aligned and propagated back to the object plane using iterative computational phase synchronization. This removes the need for rigid interferometric setups that have limited practical optical synthetic aperture systems for decades, effectively creating a virtual aperture far larger than any single sensor.

The system delivers sub-micron resolution across a wide field of view and operates from several centimeters away, overcoming the usual trade-offs between resolution, field of view, and working distance. Demonstrations have shown MASI imaging micrometer-scale details on a bullet cartridge, revealing markings useful for forensic analysis.

MASI’s design scales efficiently: adding more sensors increases capability without introducing prohibitive alignment challenges. By decoupling measurement from synchronization, the system shifts the defining factor of optical performance from physical glass to software, enabling new possibilities for forensic science, medical diagnostics, industrial inspection, and remote sensing.