Flexible, hydrogel-based transistors that can host living cells point to a new class of bio-integrated electronics, blurring the boundary between semiconductor devices and biological systems.

Researchers at The University of Hong Kong’s Wearable, Intelligent, Soft Electronics (WISE) group have developed the first soft, three-dimensional transistors that can integrate with living cells—an advance that could reshape bioelectronics and medical device design. At the core of modern electronics are silicon transistors: rigid, planar switches that drive chips in everything from phones to servers. But their stiffness limits how well they can interface with soft, living tissue.

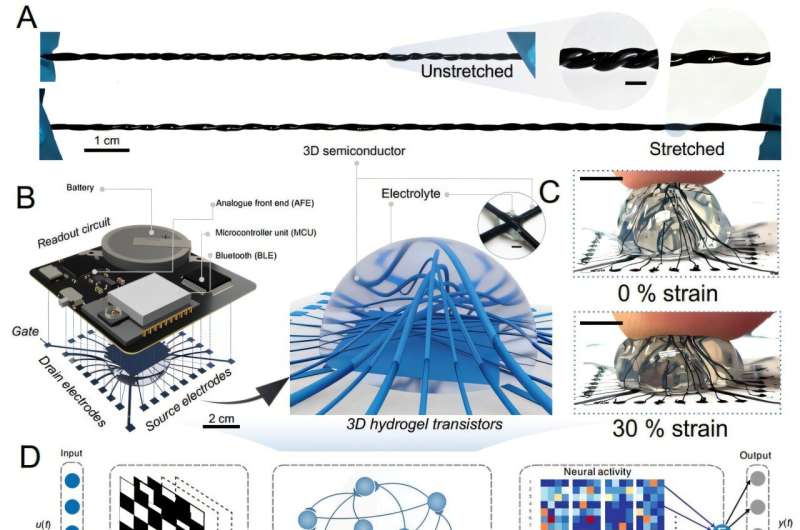

Addressing that gap, the HKU-WISE team, led by Professor Shiming Zhang, has created hydrogel-based 3D transistors that are not only pliable and biocompatible but thick enough (millimeter-scale) to host living cells directly. Unlike traditional semiconductors, these hydrogel materials are synthesized in water through a 3D self-assembly process. The resulting devices behave more like biological tissue than conventional electronics, opening avenues for integrating electrical functionality with biological systems—something rigid silicon simply can’t achieve.

Published in Science, the research marks a shift in how transistors can be conceived. Instead of being strictly electronic switches etched on flat silicon wafers, these soft 3D transistors merge structure and function in ways better suited for bio-hybrid applications.

Why this matters in electronics: Conventional transistor design has focused on scaling down and stacking silicon structures to boost performance and fit more devices into chips. Advancements like 3D transistors based on 2D materials promise energy-efficient, high-performance computing. But integrating electronics with biology requires something different—materials and device architectures that can live alongside cells without injury or rejection. The hydrogel transistors developed by HKU-WISE offer just that.

These soft devices could enable bioelectronic interfaces for health monitoring, neural prosthetics, and hybrid computing systems that blend living cells with electronic control. While still early, the approach points toward a future where electronics are no longer separate from biological environments but embedded and interactive with them. Researchers emphasize this is an initial step, with further work needed on performance, durability, and safety before practical applications emerge.