MIT engineers use heat-conducting silicon microstructures to perform matrix multiplication with >99% accuracy hinting at energy-efficient analog computing beyond traditional chips.

MIT-led researchers have unveiled an unconventional computing method that repurposes excess heat in silicon to perform matrix multiplication the core mathematical engine behind machine learning and AI models with over 99 % accuracy in early tests. This marks a potentially radical shift from traditional electronic computing paradigms toward thermal analog computation.

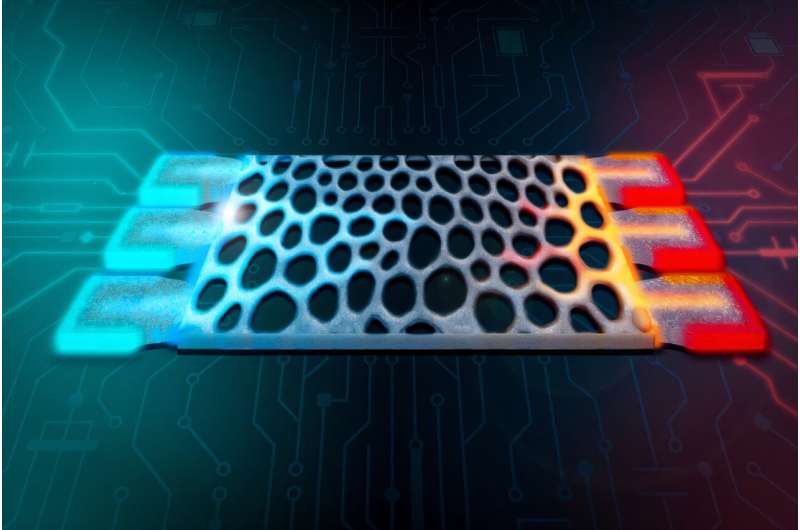

The work, published in Physical Review Applied, centers on tiny silicon structures, each roughly the size of a dust particle, designed using inverse design algorithms that tailor how heat diffuses through the material to execute specific mathematical functions. Unlike digital circuits that shuttle electrons through transistors, these structures encode input data as temperature differences, letting the natural conduction of heat carry out the computation.

Matrix multiplication a staple in training and running large language models (LLMs), neural networks, and many other AI workloads traditionally dominates both compute cycles and energy budgets in data centers and edge devices. By contrast, the thermal compute approach uses waste heat, typically a byproduct of electronics, as the information medium itself. In simulations, the team’s heat-based devices achieved more than 99 % correctness on matrix–vector multiplication tasks relevant to sensing and microelectronic diagnostics.

To design these structures, the researchers fed target matrix specifications into an optimization system that iteratively refined the silicon geometry including pores and thickness gradients so heat flow naturally performed the right numerical transformations. A key limitation arises from heat’s physical law of flowing from hot to cold: the structures inherently encode only positive coefficients. The team gets around this by splitting matrices into positive and negative parts and combining the results later.

While the proof-of-concept shows promise, significant challenges remain before this approach can compete with conventional digital accelerators like GPUs and tensor cores for large-scale AI. The structures must be tiled at massive scales for complex tasks, and current designs have limited bandwidth and scalability. Still, the research suggests promising analog and energy-aware computing opportunities especially in tasks such as thermal monitoring, heat-source detection and integrated sensing where existing electronics already contend with heat byproducts. If matured, silicon heat computing might not just augment chips but also redefine how future AI hardware harvests and reuses energy that today is wasted as heat.