What if the heat your devices produce could do the computing? New silicon structures turn waste heat into calculations, cutting energy use and extra sensors.

Modern chips waste much of their energy as heat. Managing this heat needs power, cooling hardware, and sensors. As computing demand grows, this heat problem increases. To study this, MIT researchers built silicon structures that perform calculations using waste heat instead of electricity. The goal is to turn heat inside devices into a computing signal, reducing energy use and the need for added sensing and cooling hardware.

In this method, data is stored as temperature. Heat in a device flows through a silicon structure. As it moves, the structure controls the heat flow so that a calculation occurs. The output is measured as the heat collected at the other end.

This approach can perform matrix vector multiplication, a core operation in machine learning, with over 99 percent accuracy. While it is not ready for large AI models, it can handle small computations for thermal sensing, diagnostics, and monitoring in electronic systems.

Today, chips rely on sensors and control circuits to track temperature and find hot spots. These add cost, power use, and design effort. Heat-based computing can detect heat sources and temperature changes without adding sensors or using extra energy.

The system uses software to design materials that guide heat. Engineers define the calculation first. The software then finds the structure shape that produces the needed heat flow pattern.

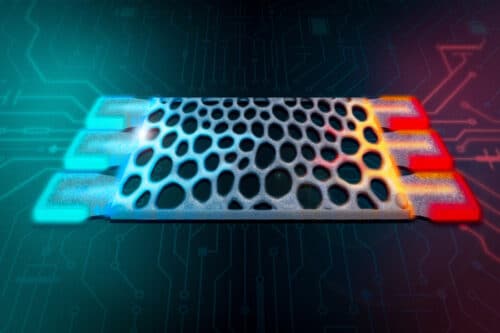

Using this method, the team created silicon structures with pores. Their geometry encodes the math. When heat passes through, the calculation happens without digital logic or electrical switching.

Because heat flows from hot to cold, the system handles only positive values. To represent negative values, the calculation is split into two parts, and the results are combined at the end. Changing the thickness of the structures allows a wider range of values.

Tests on small matrices showed accuracy above 99 percent. These calculations are enough for tasks such as fault detection, heat mapping, and temperature tracking in chips.

Scaling this approach to large models remains hard. Large systems would need many such structures, and accuracy drops as size increases. Even so, for thermal management and low-power sensing, using waste heat for computing offers direct benefit.