The approach could accelerate advancements in quantum computing, superconductors, and next-generation electronic technologies.

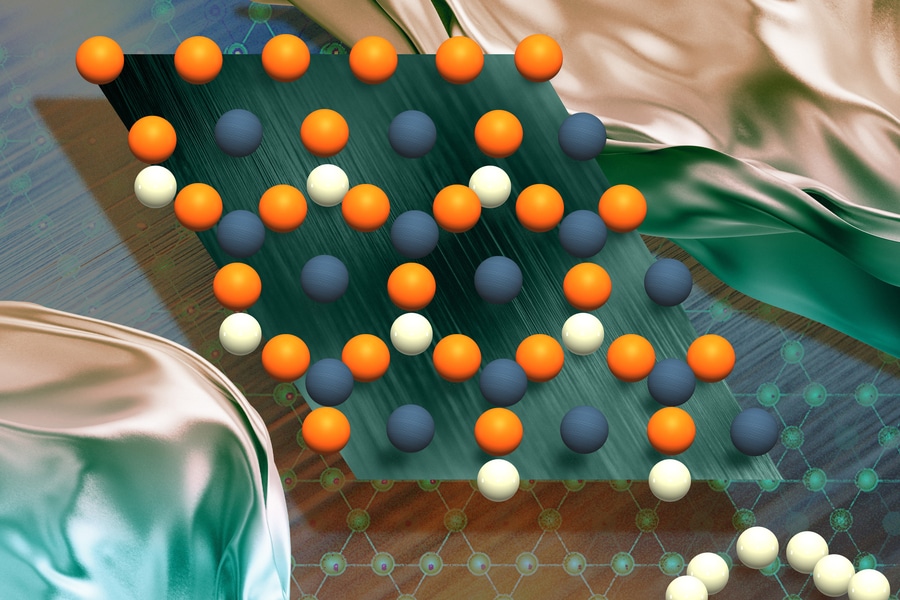

Researchers at MIT have unveiled a new method that enables generative AI models to design materials with unusual quantum properties, potentially accelerating progress in fields like quantum computing. The approach, called SCIGEN (Structural Constraint Integration in GENerative model), introduces geometric design rules into existing diffusion models so they produce materials with structures known to give rise to exotic behaviors.

This addresses a long-standing bottleneck in materials science. While AI has generated millions of stable material candidates in recent years, models typically favor safe, conventional structures rather than those with unconventional electronic or magnetic states. That leaves researchers struggling to identify candidates for quantum spin liquids and other promising quantum materials, of which only a handful have been discovered to date.

The team works by constraining generative models to follow specific lattice patterns—such as Kagome and Archimedean lattices—that are strongly linked to quantum effects. In tests, the system generated over 10 million material candidates, screened one million for stability, and ran detailed simulations on 26,000 of them. More than 40% displayed signs of magnetism. From that pool, the team synthesized two never-before-seen compounds, TiPdBi and TiPbSb, confirming that the AI predictions translated into real materials with exotic properties.

External experts agree the tool could help experimentalists prioritize promising candidates, speeding progress toward stable quantum computing platforms and other next-generation applications. The development comes as global labs race to identify materials that can support error-resistant qubits and topological superconductors. Researchers stress, however, that AI will not replace experiments: every candidate must still be synthesized and tested in real-world conditions.

Looking ahead, the team plans to extend SCIGEN to include chemical and functional constraints, opening the possibility of generating materials not only with exotic structures but also with tunable properties for energy storage, carbon capture, or advanced electronics.

“We don’t need 10 million new materials to change the world. We just need one really good material,” said MIT physicist Mingda Li, senior author of the study.