Researchers uncover how laser beams cause atomic motion in Janus semiconductors, advancing understanding of light–matter interaction for future optical and sensing devices.

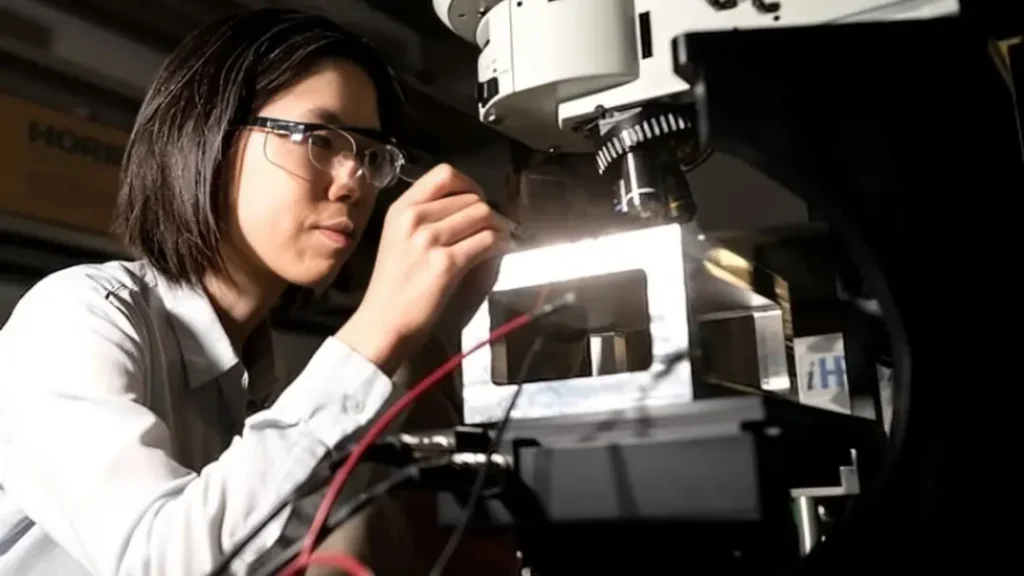

Electrons move very easily when light hits a material, and that’s the basis of photoelectric and semiconductor effects. However, researchers from Rice University observes a real shift in the positions of atoms within the crystal lattice of the material, not just the movement of electrons around them.

The laser light creates a mechanical force called optostriction. This force physically pushes or pulls the atoms slightly from their original positions. These displacements are tiny, far smaller than a nanometre but still large enough to change how the material interacts with light.

To test this property, researchers use the Janus 2D semiconductor. A Janus 2D semiconductor is an ultra-thin material made of just a few atomic layers, where the top and bottom sides contain different elements.

This uneven structure gives the material a built-in electric polarity, making it highly sensitive to light, electric fields, and mechanical forces. Because of this asymmetry, scientists can tune its optical and electronic behaviour, which makes Janus materials useful for developing flexible electronics, optical chips, and quantum devices.

The Rice University team studies a Janus material composed of two distinct layers: molybdenum sulfide selenide stacked on molybdenum disulphide. When laser light strikes it, the light does more than excite electrons.

It exerts a small mechanical force that slightly moves the atoms themselves. This process is known as optostriction, where the electromagnetic field of light physically deforms a crystal.

To observe this effect, the researchers used a method called second harmonic generation (SHG). In SHG, a material emits light at twice the frequency of the incoming laser.

The team noticed that the SHG pattern, which normally forms a symmetrical six-pointed shape reflecting the crystal’s structure, became distorted when the material was illuminated. This distortion showed that the light had pushed the atoms and altered the material’s symmetry.

Because Janus semiconductors have uneven atomic layers, their internal coupling amplifies this light-induced motion, making the shift measurable. The ability to tune such movement using light could lead to optical chips and sensors that operate without electrical current.

The study was published in ACS Nano.