A common lab tool may be distorting what we think we know about lithium batteries. A frozen twist now reveals a truer picture and it changes the story.

When something is measured it can be changed by the act of measurement. A common case is checking tire pressure. When the gauge is attached, air escapes and the pressure shifts. The same issue exists in materials research. To watch a chemical reaction inside a material, scientists fire X-rays at it, but the beam itself can trigger reactions and alter the material. This has limited progress in areas such as rechargeable batteries.

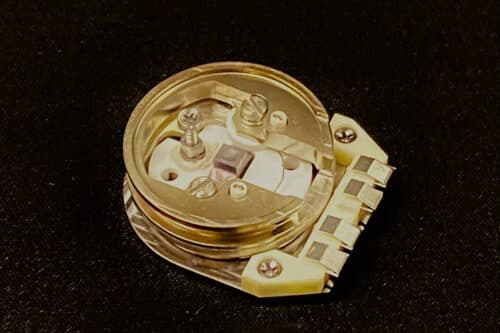

Lithium metal batteries are a key case. They can store more energy and charge fast, but they fail after a few cycles. A thin layer forms on the anode during the first cycle. It lets lithium ions pass and blocks electrons. This layer controls battery life and safety. To examine it, researchers use X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Standard XPS is done at room temperature in a vacuum. Under those conditions the layer composition changes and becomes thinner, so the tool overwrites what it is supposed to read.

A Stanford team changed how the same method is used. They froze battery samples right after the layer formed at −200 °C. They then examined the layer at about −110 °C using XPS. Under these cold conditions the layer remained unchanged. Using both standard XPS and the frozen version called cryo XPS, the team studied how batteries perform with different electrolytes. Standard XPS gave weak links between the chemistry of the layer and battery performance. Cryo XPS gave strong links. This means the frozen method yields data that better reflects the real state of the interface during operation.

They also saw that standard XPS signals can mislead battery design. Standard XPS showed high lithium fluoride in the layer, which is linked to longer battery life. Cryo XPS showed much less. The same mismatch appeared with lithium oxide. This suggests that some past design choices may rest on distorted data.

Lithium metal batteries have high energy potential but suffer from safety and life cycle issues that come from this thin protective layer. With a more accurate view of what the layer contains during use, researchers can design better electrolytes or coatings to stabilize it. The work also calls into question past interpretations made using room temperature XPS. The cryo method gives a more faithful picture and could support progress in other batteries and in unrelated materials where the probe itself changes what is measured.