The low-cost, battery-free sensor harvests energy from sweat and sends real-time data wirelessly, pointing to a future where everyday objects, not wearables, quietly track our health.

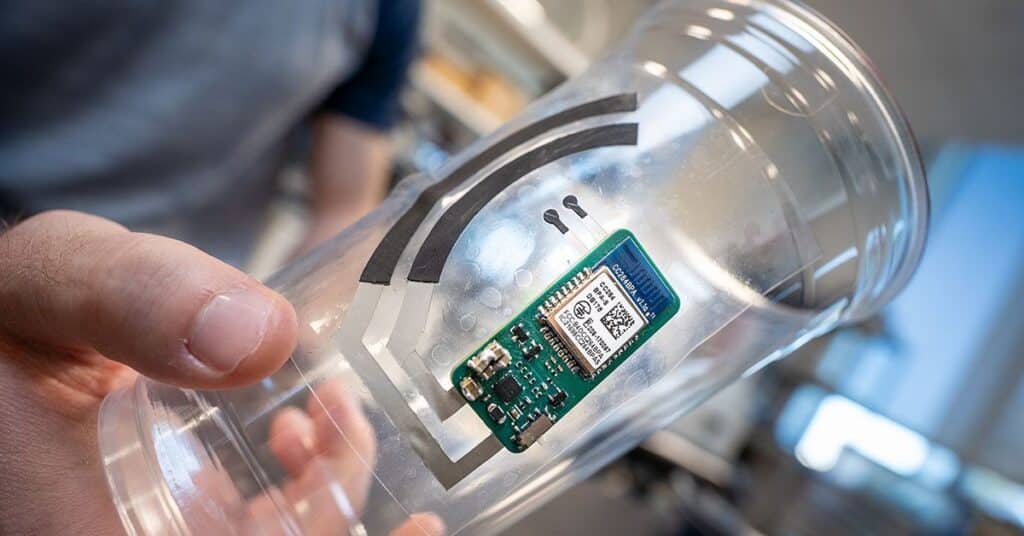

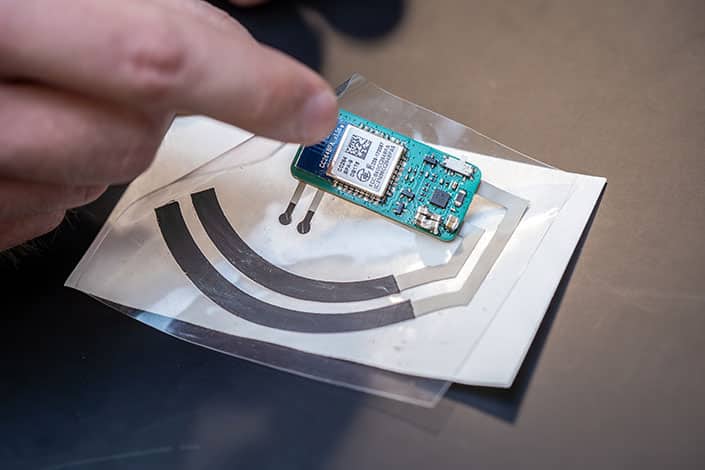

Researchers at University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego) have developed a novel, battery-free electronic sticker that transforms a simple drinking cup into a health sensor capable of monitoring vitamin C levels via fingertip sweat.

The flexible adhesive device attaches to the outside of any cup or bottle. When you grip the container, a porous hydrogel patch on the sticker collects trace amounts of sweat from your fingertips. A built-in bio-fuel cell then converts chemicals in the sweat into electricity, which powers a printed circuit board and a vitamin C sensor. The data are wirelessly sent—via Bluetooth Low Energy—to a nearby laptop or other device.

Vitamin C is crucial for immune function, tissue repair and iron absorption, yet standard testing methods require blood draws, lab equipment and often a cost of around US$50 per test. The new sticker offers a low-cost, convenient alternative: because it harvests energy from sweat and needs no battery, it could cost just a few cents per unit, making frequent or even continuous nutritional monitoring feasible.

In lab trials, the team stuck the sticker onto disposable cups and tracked vitamin C changes after participants either took supplements or drank orange juice. The system ran for more than two hours using only sweat-derived energy.

Beyond this proof-of-concept, the researchers say this is a step toward what they call “un-wearables”—objects that monitor health unobtrusively, embedded into everyday items so users don’t have to think about wearing or operating them. Their next goal: expand the system to detect other nutrients or biomarkers, and wire the sticker to smartphones or smartwatches for real-time tracking. If successfully scaled and commercialised, such technology could democratise access to nutritional health data, especially in low-resource settings where lab tests are impractical. It also signals a shift in how we think about health sensors—not just wearables on the body, but sensors built into objects we use every day.