A decade-old claim about a near-miracle ultrathin insulating coating for electronics overturned leakage, not super-insulation, drove the surprising results.

In the world of microelectronics, thinner insulating layers (dielectrics) are a big deal. They help capacitors store more charge and let transistors switch faster, both crucial for high-performance chips. A material with an exceptionally high dielectric constant (“k”) could let designers pack more functionality into tiny spaces. But new research reveals that a widely-cited ultrathin coating once thought to be a breakthrough insulator was actually mischaracterized due to hidden leakage.

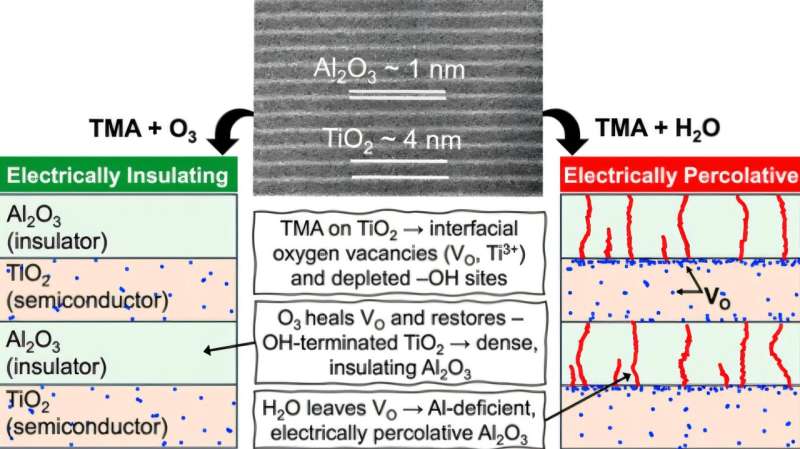

Back in 2010, a research team at Argonne National Laboratory reported a nanolaminate dielectric made from alternating layers of aluminum oxide and titanium oxide that appeared to have a giant dielectric constant near 1,000 orders of magnitude higher than conventional materials. That result sparked follow-on work exploring similar ultrathin stacks for advanced electronics.

But a recent study published in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces re-examined this system and found the giant k was an illusion. Instead of acting as a robust insulator, the nanolaminate allowed charge to leak through microscopic pathways, giving the false impression of high charge storage. Essentially, the measurement interpreted leakage paths as dielectric behavior.

The culprit turned out to be the chemistry at the earliest atomic layers. In the original design, the first aluminum oxide sublayers didn’t fully form at the atomic scale, leaving weak spots that let electrons slip through. These flaws weren’t visible under the microscope but were enough to distort electrical measurements.To fix this, researchers tweaked the deposition process. Instead of using water as the oxygen source during atomic-layer deposition, they switched to ozone. The stronger oxidizing environment helped complete the aluminum oxide layers even at sub-nanometer thicknesses, sealing leakage paths and producing a coating that behaved like a real insulator.

The study underscores a key lesson for ultrathin electronics: at atomic scales, chemistry can be just as important as layer thickness. Apparent breakthroughs need rigorous validation, especially when tiny leaks can masquerade as revolutionary properties.