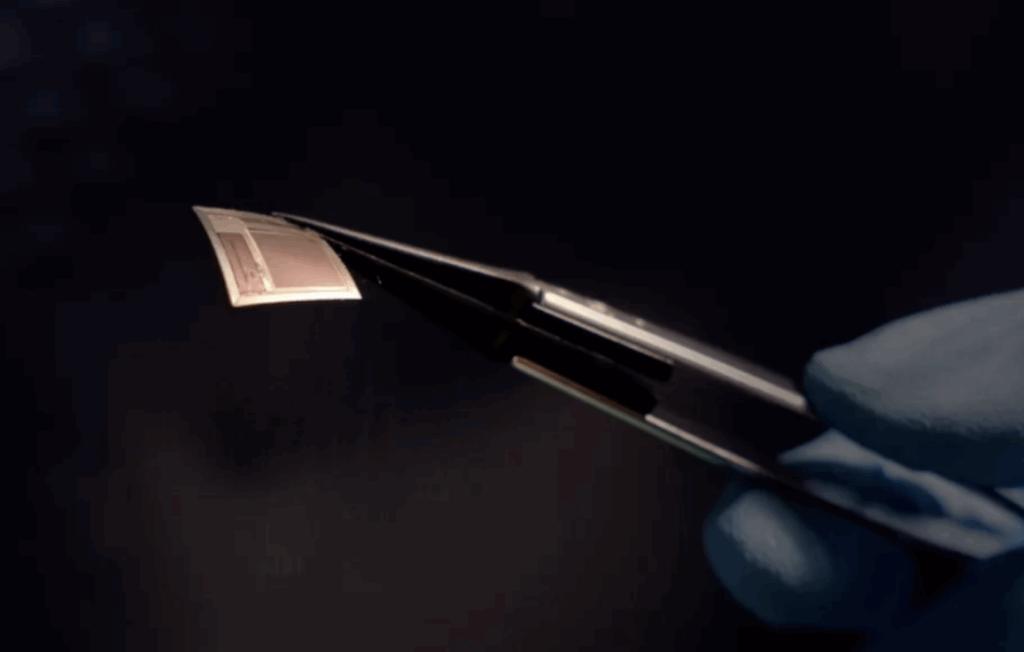

A fingernail-sized silicon implant with 100× higher wireless bandwidth and 65,000+ electrodes is redefining brain-computer electronics, paving the way for minimally invasive neuroprosthetics and AI-driven neural decoding.

Credit: Columbia Engineering

A paper-thin brain implant that streams neural data at record bandwidths could reset the trajectory of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), promising faster, safer, and far less invasive treatment paths for epilepsy, paralysis, ALS, stroke, and sensory loss. Researchers from Columbia University, Stanford University, NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, and the University of Pennsylvania have unveiled a fully integrated BCI fabricated as a single silicon chip eliminating the bulky electronics canisters that typically require major skull surgery. The system, called the Biological Interface System to Cortex (BISC), represents one of the most compact, high-throughput neural interfaces ever demonstrated.

The chip, just 50 μm thick and about as large as a fingernail slides into the thin space between skull and brain, conforming like “wet tissue,” according to the engineering team. Despite its size, it packs 65,536 electrodes, 1,024 recording channels, and 16,384 stimulation channels into a 3 mm³ CMOS device. A battery-powered wearable relay station beams power in and neural data out, using a custom ultrawideband link capable of streaming at 100 Mbps roughly 100× the throughput of current wireless BCIs. The relay further bridges data to standard Wi-Fi, effectively putting the brain on a network.

By collapsing amplifiers, converters, radio, power management, and digital control into one die, the chip removes the wires, caps, and connectors that complicate surgery and degrade signals over time. Early trials in motor and visual cortex models show stable, high-resolution recordings suitable for machine-learning pipelines that decode intention, perception, or mental states. Surgeons report that the device can be inserted through a minimally invasive skull opening and placed subdurally without penetrating tissue.

The platform also includes its own instruction set and software stack, positioning the chip as a computing architecture for neural decoding and neurostimulation. The extreme miniaturization opens the door to multimodal implants that might one day combine electrical, optical, or acoustic interfaces on a single substrate. To accelerate translation, the team has formed Kampto Neurotech to commercialize research-grade versions and pursue human applications. As AI systems increasingly rely on real-time biological signals, the researchers say chip-scale BCIs like BISC could redefine how humans recover lost abilities and how future machines and brains communicate.

Ken Shepard, Lau Family Professor of Electrical Engineering at Columbia University explained that “most implantable systems are built around a bulky canister of electronics that takes up enormous space inside the body. Our implant, by contrast, is a single ultrathin integrated-circuit chip that can slide into the narrow space between the brain and the skull, resting on the brain like a piece of wet tissue paper.”

Dr. Brett Youngerman, assistant professor of neurological surgery at Columbia University and neurosurgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center mentioned “this high-resolution, high-data-throughput device has the potential to transform how we manage neurological conditions, from epilepsy to paralysis.”