The approach promises faster, smaller, and more reliable devices for next-generation computing, neuromorphic systems, and solar technologies.

A research team at Rice University has unveiled a transfer-free method to grow ultrathin semiconductors directly onto electronic components, removing one of the biggest barriers in next-generation device fabrication.

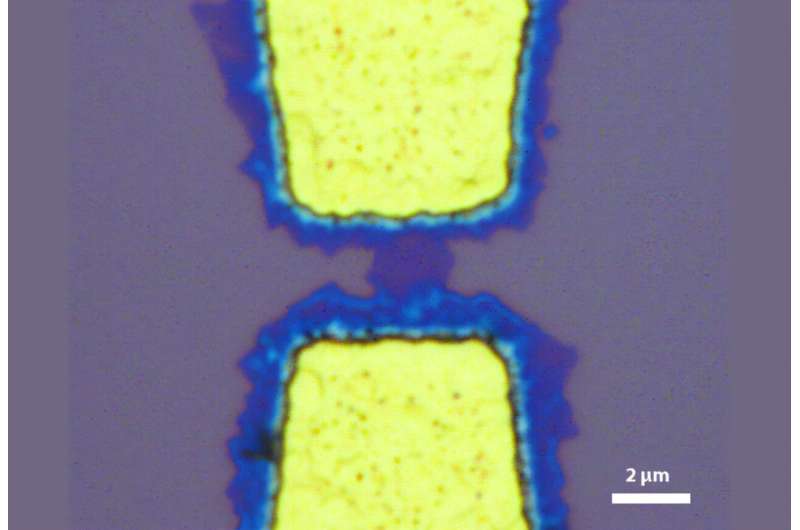

The method uses chemical vapor deposition (CVD) to grow tungsten diselenide—a two-dimensional (2D) semiconductor—directly on patterned gold electrodes. Traditionally, such materials are grown at high temperatures on one substrate and then painstakingly transferred onto another. Rice’s process bypasses this fragile transfer step and was demonstrated by fabricating a proof-of-concept transistor.

Conventional transfer techniques often damage delicate 2D films, undermining performance. By guiding semiconductor growth directly on metal contacts, the Rice team preserved material quality and reduced synthesis temperatures, protecting vulnerable components from degradation. “This is the first demonstration of a transfer-free method to grow 2D devices,” said doctoral researcher Sathvik Ajay Iyengar.The discovery began with a chance observation: tungsten diselenide preferentially formed on gold during a routine experiment. By deliberately patterning electrodes, the team harnessed this phenomenon for controlled, scalable device fabrication.

The approach could accelerate the integration of 2D materials into high-performance transistors, neuromorphic computing, solar cells, and next-generation electronics. Eliminating transfer not only simplifies fabrication but also improves electrical contact quality, scalability, and compatibility with diverse materials—critical factors for industry adoption.The study also highlights the power of international collaboration. Sparked during a U.S.–India research initiative and supported by the Quad Fellowship, the project shows how global partnerships in STEM and diplomacy can inspire cost-effective, practical solutions.

As the semiconductor industry pursues ever-smaller, faster components, Rice’s transfer-free method offers a simpler, more robust route to manufacturing ultrathin materials—paving the way for breakthroughs that could reshape computing and electronics worldwide.“The absence of reliable, transfer-free methods has been a major barrier,” noted alumnus Lucas Sassi. They claim that the work could unlock new opportunities for atomically thin devices.