By using light instead of electrical connections, the implant can work deep in the brain without damaging tissue or triggering immune responses.

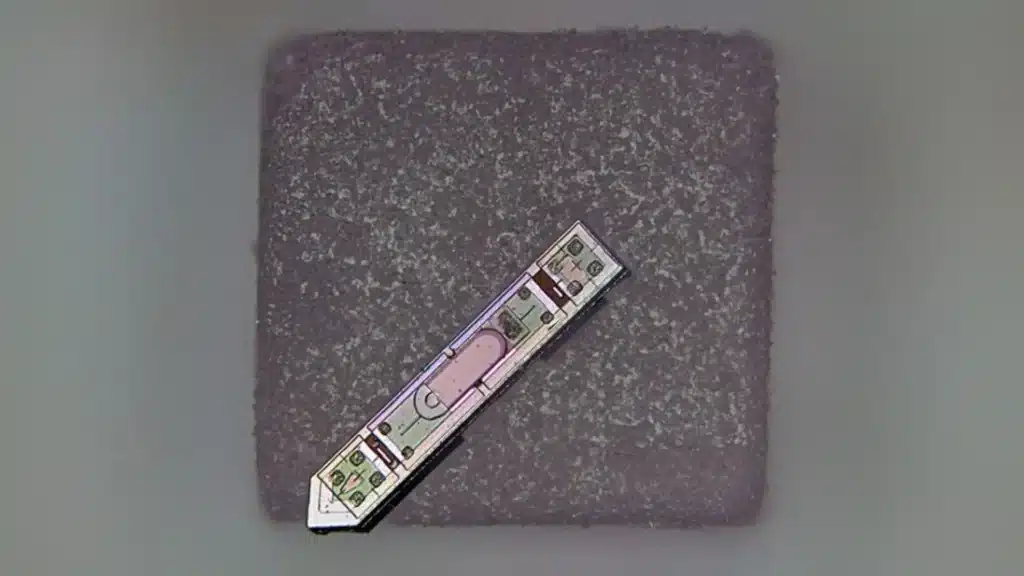

A brain implant smaller than a grain of salt can record and transmit neural activity wirelessly for more than a year, marking a major development in long-term brain monitoring research. The device, developed by researchers at Cornell University, is called a microscale optoelectronic tetherless electrode, or MOTE. It enables continuous tracking of brain signals without wires or bulky equipment.

It operates using harmless infrared laser beams that pass through brain tissue to power the circuit. The same light energy is also used to send data back through tiny pulses of infrared light that encode electrical signals from neurons. This design allows the device to function inside the brain without batteries or cables, reducing interference with tissue.

Built from aluminium gallium arsenide, the implant’s semiconductor diode captures light for power and emits it for communication. It also includes a low-noise amplifier and optical encoder based on standard microchip technology, enabling precise signal recording with minimal energy use.

The device is tested first in cell cultures and later implanted in mice, targeting the brain region responsible for processing sensory input from whiskers. Over a year, it consistently records both neuron spikes and broader synaptic signals, all while the animals remain healthy. The small size and wireless operation aim to avoid irritation caused by larger electrodes or optical fibres, which can trigger immune responses in brain tissue.

The MOTE’s design may also support data collection during MRI scans, which is not possible with traditional implants. Researchers plan to adapt the system for spinal cord studies and continuous neural monitoring using artificial skull plates. The full study appears in Nature Electronics, highlighting progress toward long-term, minimally invasive brain–machine interfaces.