Can light perform millions of calculations at once without extra materials? A new optical system shows how this can be done.

Performing nonlinear computations using light has long been a major challenge in optical computing. Nonlinear operations are essential for tasks such as machine learning, pattern recognition, and general-purpose computing, but most optical approaches struggle because nonlinear effects in materials are typically weak, slow, or require high power. This limitation has made it difficult to build fast, compact, and energy-efficient optical systems capable of handling large-scale nonlinear tasks.

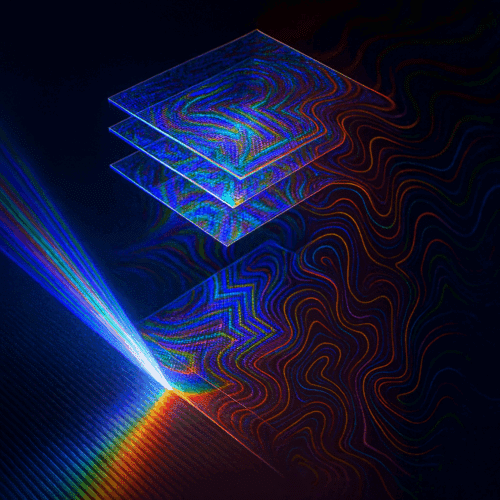

Researchers at UCLA addressed this problem by developing an optical computing system that performs large-scale nonlinear calculations using only linear materials. The system works by encoding input variables into the phase of light waves and passing them through a fixed, optimized diffractive architecture composed entirely of linear, phase-only layers. Each output pixel represents a different nonlinear function, enabling dense and parallel computation in a compact optical setup. This approach demonstrates that nonlinear computation can emerge from purely linear optical interactions when information is structured in the phase of light.

The team established both theoretical and experimental evidence showing that diffractive processors can act as universal nonlinear function approximators. They can realize any bandlimited nonlinear function, including multi-variable and complex-valued functions, and replicate common neural network activations such as sigmoid, tanh, ReLU, and softplus. Numerical simulations demonstrated the parallel computation of one million distinct nonlinear functions at wavelength-scale spatial density, and experiments using a spatial light modulator and an image sensor confirmed simultaneous execution of tens of nonlinear functions.

The framework is scalable to larger systems using high-resolution image sensors with hundreds of megapixels, potentially enabling the computation of hundreds of millions of nonlinear functions in parallel. This approach could transform ultrafast analog computing, neuromorphic photonics, and high-throughput optical signal processing, offering engineers and researchers a powerful new method for performing nonlinear computations without relying on nonlinear optical materials or electronic post-processing.