A thermoelectric film can harvest enough energy from the tiny temperature difference between skin and air to light an LED, marking one of the strongest steps yet toward self-powered wearables and ultra-low-power sensors.

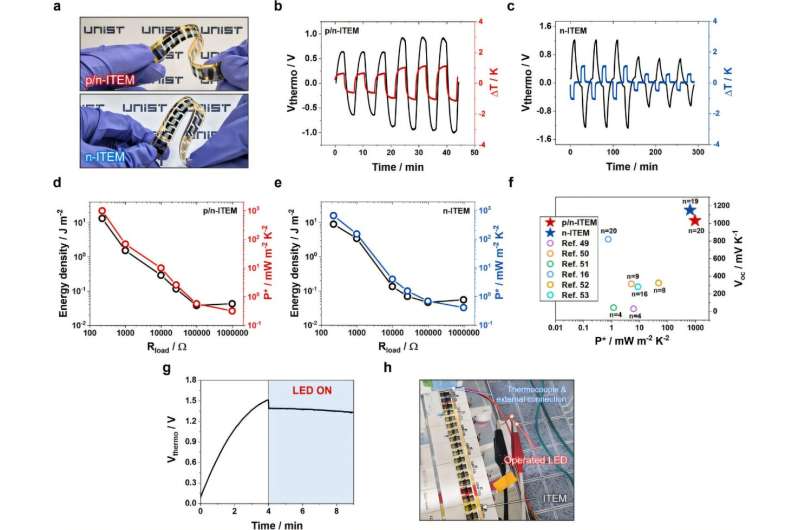

A research team in South Korea has demonstrated an ionic thermoelectric (TE) film that can light an LED using only the tiny temperature difference between human skin and the surrounding air, sometimes as low as 1.5°C. The development marks one of the most efficient demonstrations of body-heat energy harvesting to date, pointing to a future of self-powered wearables and ultra-low-power sensors.

The team reported record performance for both p-type and n-type ionic TE polymers, achieving ionic figures of merit (ZTi) of 49.5 and 32.2, respectively, roughly a 70% leap over earlier materials. That efficiency gain is crucial because real-world wearables rarely see temperature gradients above a few degrees, making conventional thermoelectrics impractical for skin-mounted devices.

Thermoelectrics convert heat to electricity by moving charge carriers from hot regions to cold ones. In the ionic version of this mechanism, protons migrate in p-type materials, while chloride ions move in n-type formulations. When engineered correctly, this ion flow produces usable voltage even under extremely small gradients. The new films, engineered as thin flexible composites, optimize ion concentration and diffusion using a thermodynamic design strategy that the researchers say has been missing in earlier generations of ionic TE research.

The p-type film uses a conductive PEDOT:PSS composite, while the n-type incorporates copper chloride. Both remain lightweight, bendable, and manufacturable at scale, enabling configurations suited for wearables. In testing, a module with ten p–n pairs wired in series generated more than 1.03 V from just a 1°C difference, enough to illuminate an LED at a 1.5°C gradient. Stability tests showed over 95% performance retention after two months of indoor operation, addressing a long-standing concern about drift in ionic systems.

Beyond the lab demo, the work provides a framework for designing next-generation ionic thermoelectrics using controlled additive tuning and structural optimization. For ultra-low-power electronics, the implications are significant: skin-mounted patches that run without batteries, smartwatches powered by body heat, and distributed IoT sensors scavenging micro-gradients in ambient environments. With energy harvesting climbing the priority list for wearables and medical telemetry, the research signals a new directionone where even the faint warmth of the human body can become a practical power source.