New research suggests some biodegradable electronic materials persist in soil for years, breaking down into microplastics that could create a fresh environmental challenge instead of solving e-waste.

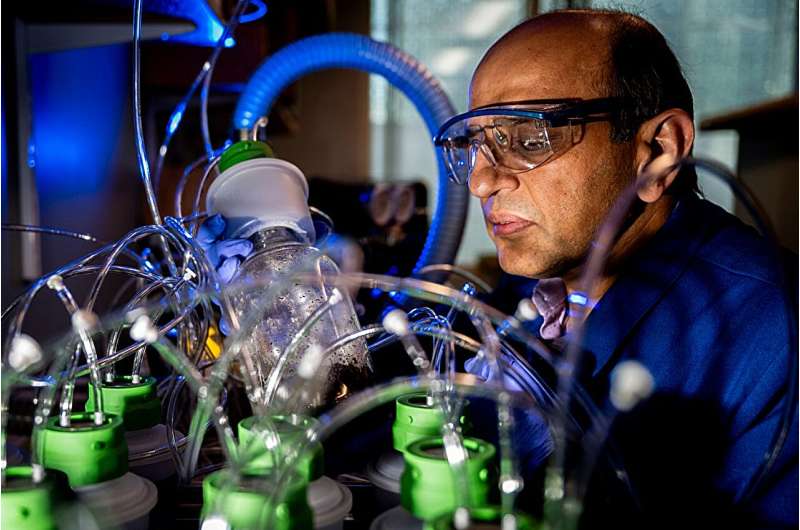

Biodegradable electronics once hailed as an eco-friendly solution to growing e-waste could be introducing a new environmental threat: persistent microplastic pollution. Researchers at Northeastern University found that materials commonly used in transient electronics can break down into microplastic fragments that linger in soil for years, challenging assumptions about the environmental benefits of “dissolvable” devices.

At the core of the finding is PEDOT:PSS, a polymer widely used in flexible and biodegradable electronic components, including some medical devices. Instead of fully degrading, the polymer persists for over eight years in soil conditions and fragments into microplastics tiny particles increasingly linked to ecological disruption and health concerns.

The research evaluated both partly and fully degradable devices. It showed that outcomes vary widely depending on material choice: natural polymers like cellulose or silk fibroin degrade faster and produce fewer harmful byproducts, while synthetic polymers can persist and pollute. Scientists caution that the issue isn’t limited to electronics. Other studies show that many biodegradable plastics in consumer products also generate microplastics during breakdown, especially outside ideal industrial composting environments. These particles can remain in ecosystems and soil long after the original product has “biodegraded.”

Aside from degradation products, the researchers highlight manufacturing concerns. Current electronics fabrication is resource-intensive and linear heavy in water and chemical use counteracting potential environmental gains from biodegradability. There’s growing consensus that addressing end-of-life impacts requires rethinking both materials and production models.

Industry adoption of transient electronics has accelerated over the past decade, especially in medical wearables and disposable sensors. But these new findings suggest that without careful material selection and standards for byproduct safety, biodegradable electronics could trade one waste problem for another. Researchers advocate for circular design approaches and expanded testing of degradation byproducts, not just end-of-life dissolution. Prioritizing materials that fully mineralize without releasing persistent microplastics will be key to fulfilling the promise of truly sustainable electronics.