A lithium battery could let electric vehicles drive farther on a single charge stay reliable in winter and reduce battery size while holding more energy.

Could an electric vehicle drive from Seoul to Busan and back on a single charge? Could drivers stop worrying about battery performance in winter? A Korean research team may have found an answer. They developed an anode-free lithium metal battery that can nearly double driving range without increasing battery size.

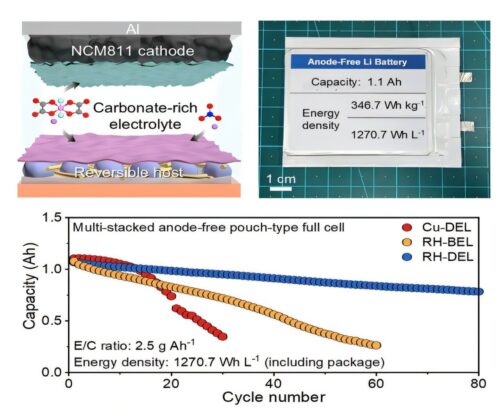

A research team at POSTECH, KAIST, and Gyeongsang National University achieved a volumetric energy density of 1,270 Wh/L in an anode-free lithium metal battery. This is nearly double the 650 Wh/L typical of lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles.

Anode-free lithium metal batteries remove the conventional anode. During charging, lithium ions from the cathode deposit directly onto a copper current collector. By cutting out components, more space inside the battery is used for energy storage, similar to fitting more fuel into the same-sized tank.

This design faces challenges. Uneven lithium deposition can create dendrites, raising the risk of short circuits and safety hazards. Repeated charging and discharging can also damage the lithium surface, reducing battery life.

To tackle these problems, the team used a two-pronged approach: a Reversible Host (RH) and a Designed Electrolyte (DEL). The RH is a polymer framework with distributed silver (Ag) nanoparticles that guide lithium to deposit in specific spots instead of randomly, like a parking lot ensuring orderly placement.

The DEL adds stability by forming a thin protective layer of Li₂O and Li₃N on the lithium surface. This layer prevents dendrite growth while keeping pathways open for lithium ions to move.

The RH–DEL system showed strong performance. At high areal capacity and current density, the battery retained 81.9% of its initial capacity after 100 cycles and achieved an average Coulombic efficiency of 99.6%. This enabled a volumetric energy density of 1,270 Wh/L in anode-free lithium metal batteries.

The performance was validated in laboratory cells and pouch-type batteries, which are closer to real-world electric vehicle applications. Even with minimal electrolyte and low stack pressure, the batteries operated stably. This indicates potential for reducing battery weight and size while lowering manufacturing complexity, improving commercial viability.