Raindrops can now create electricity to run city drains and flood alerts. See how rain alone could help cities handle storms without extra power.

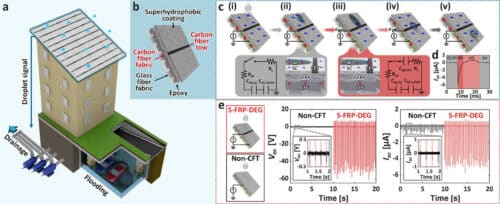

Cities and urban areas face challenges managing heavy rain and preventing flooding. Current drainage systems often depend on external power and manual monitoring, which can fail during storms. To address this, a research team at UNIST has developed a way to generate electricity from raindrops hitting rooftops and pipes, enabling automated drainage systems and flood alerts without relying on outside electricity.

The team created a droplet-based electricity generator (DEG) made from carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP), called the superhydrophobic fiber-reinforced polymer DEG (S-FRP-DEG). CFRP composites are strong, light, and resistant to corrosion, making them suitable for long-term outdoor use on rooftops and other exposed urban structures.

The generator works like static electricity. When a positively charged raindrop hits its negatively charged superhydrophobic surface, it transfers charge as it quickly rolls off. This motion produces an electric current in the embedded carbon fibers, generating power almost instantly. Unlike metal-based droplet generators, which can corrode from moisture and pollution, the CFRP design remains reliable in harsh conditions. Efficiency is further improved by adding a textured surface and a lotus-leaf-inspired coating that repels water and prevents dirt buildup.

In lab tests, a single raindrop of about 92 microliters produced up to 60 volts and a few microamps of current. Connecting four units in series briefly powered 144 LED lights, showing the system can be scaled up. Outdoor tests on rooftops and drainage pipes confirmed that as rainfall increased, the electrical signals became stronger and more frequent. This allowed the system to detect light, moderate, and heavy rain and automatically activate drainage pumps when needed.

This technology allows urban infrastructure to monitor rainfall and respond to floods using only the energy of rain itself. In the future, it could also be integrated into vehicles or aircraft, where carbon fiber composites are already widely used.