Two methods from researchers at NUS and The University of Manchester have pushed graphene beyond gallium arsenide, setting world records in electron mobility and unlocking quantum effects at Earth-strength magnetic fields.

Researchers from the National University of Singapore (NUS) and The University of Manchester have achieved a milestone long thought out of reach: graphene devices with electron mobilities that not only rival but surpass the best gallium arsenide (GaAs)-based semiconductors. The twin breakthroughs address graphene’s decades-old challenge of electronic disorder, unlocking ultra-clean performance crucial for next-generation quantum and high-speed electronics.

Graphene, a one-atom-thick carbon lattice, already holds the record for room-temperature electron mobility. Yet, at cryogenic temperatures, GaAs-based systems have consistently outperformed it—thanks to years of refinement and fewer electron-scattering imperfections. The stumbling block has been charge fluctuations from surrounding materials, which create “electron-hole puddles” that limit graphene’s mobility.

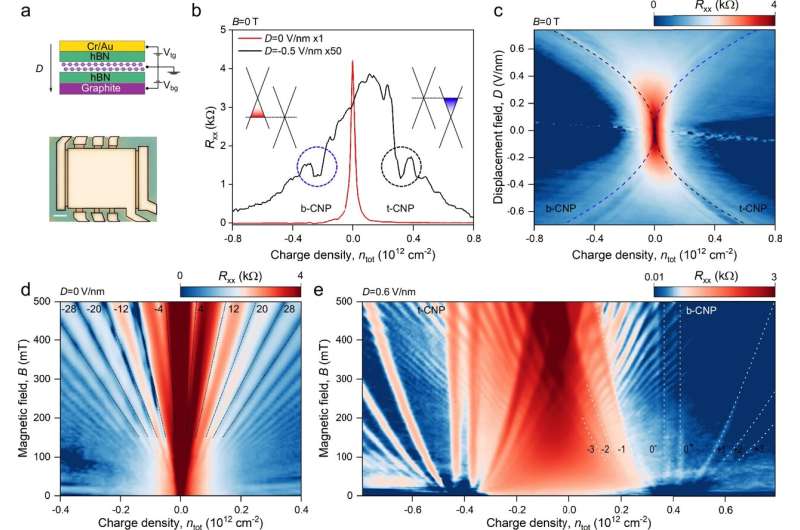

Now, two complementary methods reported this month redefine the playing field. Researchers developed a strategy using large-angle twisted bilayer graphene as an electrostatic shield. By twisting two graphene sheets 10°–30° apart, one could be doped to screen stray electric fields while remaining electronically decoupled. This reduced charge inhomogeneity tenfold and enabled hallmark quantum effects—like Landau quantization—at magnetic fields nearly 100× weaker than before. Transport mobilities exceeded 20 million cm²/Vs, surpassing GaAs benchmarks.

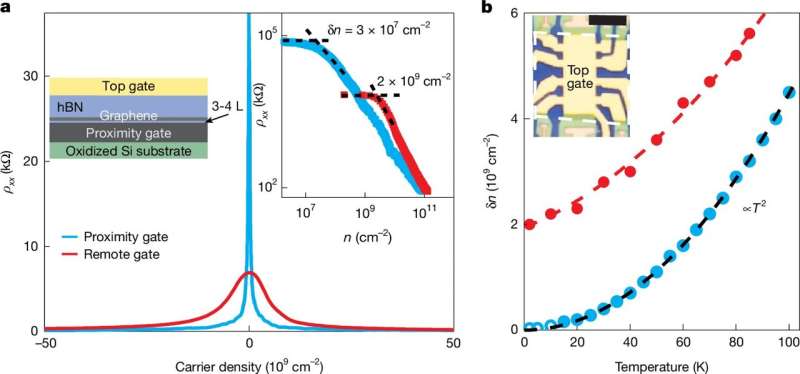

A Manchester-led team headed by Nobel Laureate Sir Andre Geim used proximity metallic screening. Graphene was placed less than a nanometer from a graphite gate, separated by ultrathin hexagonal boron nitride. This extreme Coulomb screening yielded Hall mobilities beyond 60 million cm²/Vs—a new world record. Quantum Hall plateaus and oscillations emerged at milli-Tesla field strengths, near Earth’s magnetic field.

Both methods offer distinct advantages—tunability with twisted bilayers versus pristine observation with proximity screening—but together, they expand the experimental toolkit for two-dimensional materials. The advances promise impact in quantum metrology, ultra-sensitive sensing, and energy-efficient electronics, while setting the stage for future work on graphene-based moiré quantum systems.

“These results change what we thought was possible for graphene,” said Ian Babich, Ph.D. student at NUS. “It’s a historic moment that opens up unexplored quantum regimes.”