The new research controls the noise in atomic frequency to double the precision of atomic clocks for a more accurate time.

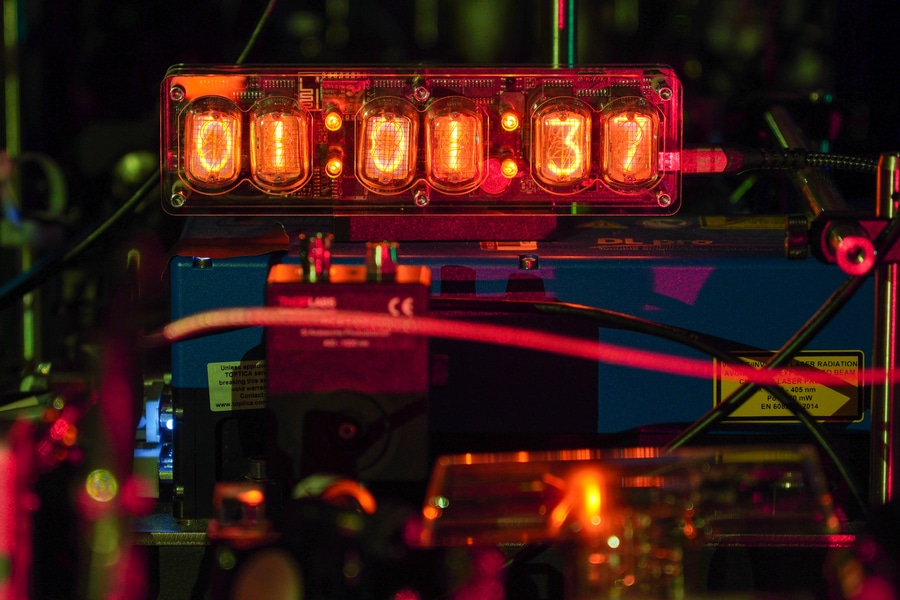

Without precise time, any electronics in the world wouldn’t work. It keeps time for GPS navigation, internet data transfer, stock trading, and communication networks. These clocks are called atomic clocks; they work by measuring how atoms naturally “frequency oscillation” at fixed, steady rates.

Most current atomic clocks use cesium atoms, which oscillate more than 10 billion times per second. Lasers match these atomic ticks to keep perfect time.

But newer optical atomic clocks use atoms like ytterbium, which tick much faster, about 100 trillion times per second. Faster oscillation means more accurate timekeeping, but these optical clocks face a problem called quantum noise. Quantum noise makes it harder to measure the tiny oscillations of atoms clearly.

The new approach doubles the precision of an optical atomic clock, enabling it to discern twice as many ticks per second compared to the same setup without the new method. Further they anticipate that the precision of the method should increase steadily with the number of atoms in an atomic clock.

MIT scientists have now developed a way to reduce this noise and make optical clocks more stable. Their new method, called global phase spectroscopy, looks at how light from a laser interacts with entangled ytterbium atoms. When the light hits these atoms, it creates a small memory of how the light and atoms interacted, called “global phase”.

Earlier, scientists thought this effect didn’t matter, but the MIT team found that it actually carries information about the laser’s frequency.

With these clocks, scientists are trying to detect dark matter and dark energy, and test whether there really are just four fundamental forces, and even to see if these clocks can predict earthquakes.

By using quantum amplification and a time-reversal technique, the researchers were able to strengthen this phase signal. This helps the clock detect smaller frequency changes that would normally be lost in noise. As a result, the new method doubles the precision of optical atomic clocks and makes their lasers more stable.