Wearable devices can read health data and use less battery. See how a new system helps tiny processors work longer and process data.

Electronic components such as sensors and microcontrollers have become small and inexpensive enough to be integrated into a range of wearable devices, which have potential in areas like health monitoring by collecting and processing data. The information these devices gather can help healthcare professionals detect medical conditions earlier and design treatment plans. While collecting data is largely a solved problem, analyzing it remains challenging because health-related data is complex, making traditional hardcoded algorithms impractical. Machine learning algorithms are often used for their ability to predict and classify patterns.

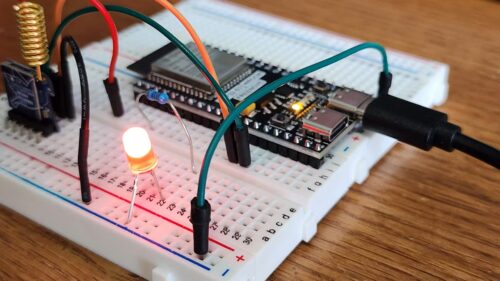

In wearable devices, low-power microcontrollers struggle to run complex algorithms, quickly hitting resource limits. Researchers at ETH Zurich have developed a system called NanoHydra, which allows these processors to run Time Series Classifications efficiently.

Time Series Classification predicts class labels from sequences of time-dependent data, such as ECG signals, brainwave patterns, or accelerometer readings. Traditional deep learning methods like convolutional or recurrent neural networks can handle these tasks but require more memory, energy, and processing power than microcontrollers can provide. NanoHydra reduces computational complexity while maintaining accuracy.

The system builds on methods called ROCKET and HYDRA, which extract features from sensor data using random convolutional kernels. NanoHydra replaces floating-point operations with binary kernels made of +1 and 1 values and substitutes functions like square roots and divisions with arithmetic shifts. This lowers energy use while keeping performance.

The researchers tested NanoHydra on GreenWaves Technologies’ GAP9 microcontroller, a chip with an eight-core cluster designed for parallel processing. By distributing the workload across cores and using SIMD operations to handle multiple data points at once, the system performs efficiently. It can classify a one-second ECG signal in 0.33 milliseconds while using 7.69 microjoules per inference, about 18 times more energy-efficient than previous methods.

NanoHydra maintains accuracy despite low resource use. On the ECG5000 dataset, it reached 94.47 percent classification accuracy, comparable to desktop-class algorithms. The team estimates that a battery-powered wearable using NanoHydra could run continuously for over four years without recharging. With long battery life and strong accuracy, devices using NanoHydra could appeal to users.