What if glucose could be measured without pain, inserts, or skin irritation? An optical device brings that possibility much closer.

Frequent glucose checks remain a major challenge for people with diabetes. Many still depend on finger-prick tests, which require drawing blood several times a day. Others use wearable monitors with a small sensor placed under the skin, but these devices can irritate the skin and must be replaced every 10 to 15 days. The need for a painless, comfortable, and reliable glucose-monitoring method has pushed researchers to explore noninvasive technologies.

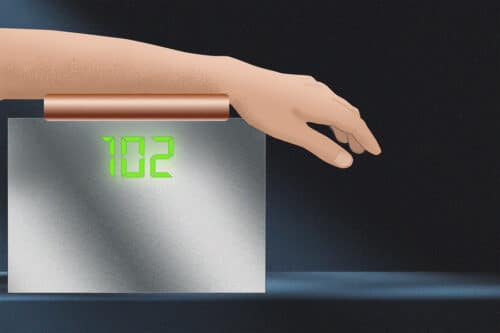

A team at MIT has now developed a noninvasive way to measure blood glucose using Raman spectroscopy. This technique identifies chemical composition by shining near-infrared or visible light on skin and studying how the light scatters from different molecules. Using this method, the group built a shoebox-sized device that can measure glucose levels without needles or implanted sensors.

In tests with a healthy volunteer, the device produced readings similar to commercial continuous glucose monitors, which rely on a thin wire inserted under the skin. Although the current prototype is too large to wear, the researchers have already created a smaller wearable version that is being tested in a small clinical study.

The team has been working on this approach for years. In 2010, they showed that glucose levels could be estimated by comparing Raman signals from interstitial fluid with a reference blood glucose reading. The method worked, but the system was too large for practical use. Later, they found a way to directly measure glucose Raman signals from the skin. Normally, the glucose signal is very weak and hard to separate from signals produced by other tissue. The group solved this by shining near-infrared light at one angle and collecting the Raman signal from another, which removed much of the background noise. That setup, however, required equipment roughly the size of a desktop printer.

The latest study focuses on shrinking the system. A full Raman spectrum contains about 1,000 spectral bands, but the researchers discovered that only three bands were needed: one glucose band and two background bands. This allowed them to remove bulky components and build a prototype about the size of a shoebox.