A tiny crystal device can now split electrons without magnets, pointing to simpler, low-power electronics and a new way to build faster, smarter chips.

Separating left- and right-handed electrons without using strong magnetic fields has been a long-standing problem in electronic device design. This limits progress in chiral electronics, a field aimed at building low-power computing and memory systems. Researchers from IIT Delhi and Germany have now demonstrated a device that solves this problem using the natural quantum properties of a crystal, rather than external magnetic control.

Many advanced electronic concepts rely on controlling electron chirality, a quantum property where electrons behave as left- or right-handed. In real materials, however, these special electrons are mixed with ordinary electrons, making them hard to isolate. Existing methods require either very strong magnetic fields or precise chemical doping, both of which add cost, complexity, and energy consumption. This has slowed the move from laboratory experiments to practical devices.

The new approach uses a palladium gallium (PdGa) crystal, where the internal quantum geometry naturally bends the motion of electrons. Instead of travelling straight, electrons drift sideways inside the crystal. Crucially, left- and right-handed electrons drift in opposite directions. This allows their separation using only an applied electric current, without magnetic fields.

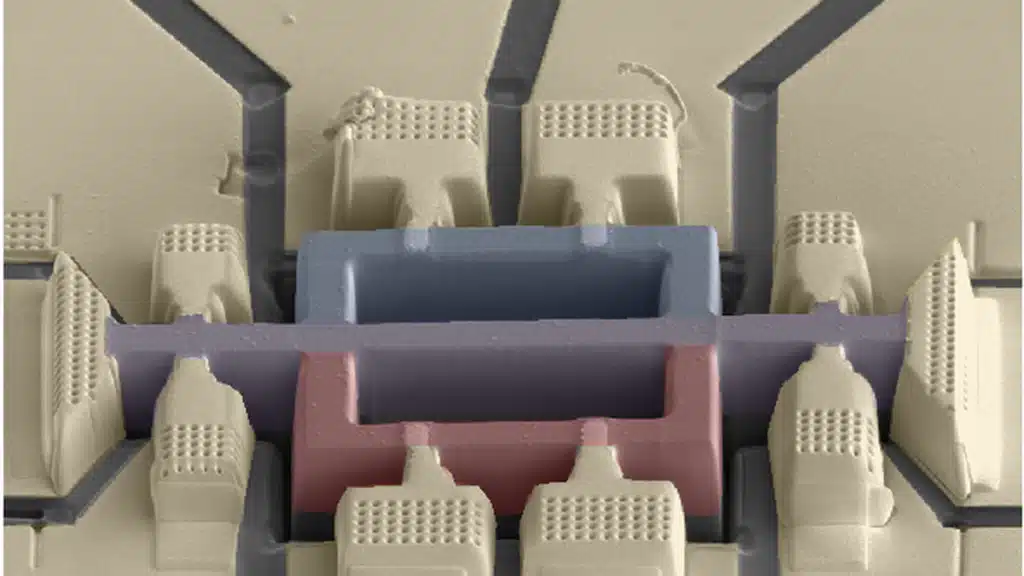

To demonstrate this, the team built a small three-arm device from the crystal. When current crossed a certain threshold, left-handed electrons flowed into one arm, while right-handed electrons flowed into another. This showed that chirality can be detected and controlled directly using electrical signals, a key requirement for practical electronic systems.

The device still faces practical limits. Fabrication currently requires ion beams, and operation needs very low temperatures. These factors restrict real-world deployment. If these challenges are overcome, the technology could support ultra-low-power logic circuits, new types of magnetic memory, and energy-efficient computing systems.